Thomas Jefferson drafted the Report on the American Fisheries with the help of Hamilton’s Assistant Secretary of the Treasury, Tench Coxe. Coxe supplied Jefferson with evidence from the leading Philadelphia shipper, Joseph Anthony, that the cod ships with profit sharing were more productive than those with fixed wages. In the end, Washington’s law not only required a written contract between captain and crew to practice broad-based profit sharing as a condition to receive the tax cuts, and it also said that the tax credits would be paid five-eighths to the crew and three-eighths to the shipowners. The credits relieved the sailors and owners of tariffs, essentially tax payments they had to make on supplies for the fishery. This is the first documented case in American history where the government made citizen shares—a form of inclusive capitalism—a condition for receiving a tax break. It was also the first time in American history that national leaders, the leaders of a major industry, and ordinary working people debated the shape of American business and how government should seek to encourage economic development.

The cod fishery law reflected the beliefs of many of the Founders that a representative republic required broad-based property ownership—typically land, or, in the case of the cod fishery, shares of profits—and a thriving middle class if the nation was to have a future based on real political liberty. Many craftspeople at the time actually owned their own businesses and shared in all the profits. In 1788, Washington said that “America … will be the most favorable country of any kind in the world for persons … possessed of moderate capital … and will not be less advantageous to the happiness of the lowest class of people because of the equal distribution of property.” His statement referred to the fact that most citizens could easily acquire enough land to support their families and achieve some economic independence.

James Madison said that the U.S. had “a precious advantage also in the actual distribution of property, and in the universal hope of acquiring property.” John Adams repeatedly sounded the alarm on inequality—specifically that he believed the concentration of wealth in property ownership would lead to the concentration of political power, which would undo a republic. In fact, while Adams drafted the new Massachusetts Constitution, some of his political colleagues considered changing the name of that state to Oceana, the fictional commonwealth of political philosopher James Harrington, where wide property ownership helped secure political liberty. Like all the Founders, Adams wanted property rights protected and he wanted everyone to be a property holder.

Land was the main form of capital at this time, and the Founders’ preferred idea of spreading capital ownership through land was expressed in repeated far-reaching governmental actions. Washington asked Jefferson to draft a liberal approach to the sale of public lands to citizens which commenced, albeit with some complications. They moved against the institution of primogeniture, a key plank of European feudalism, and with the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, they all agreed to abolish servitude in what would become Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin, and part of Minnesota, so that citizens could easily acquire land in that part of the young country (though slavery would remain a terrible evil for many decades to come in other parts of the nation).

When he became president, Jefferson acquired one million square miles of land through the Louisiana Purchase with the idealistic goal of further encouraging broad farm ownership and, in his words, securing “an empire of liberty.” For more than a half-century, up to the Civil War, federal leaders’ approach to land sales generally allowed low prices, installments, and credits in order to facilitate the wide sale of public land shares to citizens. Homesteads were the most popular economic policy of the 19th century across the political spectrum after being pushed by senior Democrats. Politicians who argued for selling land to the highest bidder and using the funds for the federal budget were drowned out. Finally, in 1862, after definitively accepting the position that land capital was for the people, Republican President Abraham Lincoln said he was for “the greatest good for the greatest number” and he signed The Homestead Act into law.

Abraham Lincoln: "In my present position I could scarcely be justified were I to omit raising a warning voice against this approach of returning despotism. It is not needed nor fitting here that a general argument should be made in favor of popular institutions, but there is one point, with its connections, not so hackneyed as most others, to which I ask a brief attention. It is the effort to place capital on an equal footing with, if not above, labor in the structure of government. It is assumed that labor is available only in connection with capital; that nobody labors unless somebody else, owning capital, somehow by the use of it induces him to labor. This assumed, it is next considered whether it is best that capital shall hire laborers, and thus induce them to work by their own consent, or buy them and drive them to it without their consent. Having proceeded so far, it is naturally concluded that all laborers are either hired laborers or what we call slaves. And further, it is assumed that whoever is once a hired laborer is fixed in that condition for life. Now there is no such relation between capital and labor as assumed, nor is there any such thing as a free man being fixed for life in the condition of a hired laborer. Both these assumptions are false, and all inferences from them are groundless. Labor is prior to and independent of capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration."

"What Abraham Lincoln Had To Say About Occupy Wall Street"

The Homestead Act allowed citizens, many of whose descendants now live in states in the West and mid-West, to acquire 160 acres of public land by building a structure and working the land. Women and ultimately African-Americans began to participate as homesteaders. Subsequently, based on the amount of land capital needed to comfortably support a family, the size of the homesteads were markedly increased until the last homestead was claimed in Alaska in 1986. Individual states—including the Republic of Texas, which had homesteads up to 320 acres—passed additional homestead acts. The broad-based property ownership approach of most of the nation’s first century achieved some of the leaders’ goals, but an important question remained: would ownership of land be an effective way to allow future generations of the working and middle class to acquire capital as the economy changed? In 1829, in retirement, former President James Madison sought to answer this question when he projected both the American population and the amount of farmland one hundred years into the future. He realized that broad-based land ownership as a basis for the republic was at serious risk because there was not enough land to go around, and he warned that our “institutions and laws must be adapted” to solve the problem that “will require for the task the wisdom of the wisest patriots.”

Later, one of those wise men stepped up to the plate—Rep. Galusha Grow, a staunch anti-slavery Republican from Pennsylvania, the Speaker of the House of Representatives who managed the Homestead legislation through Congress for President Lincoln, and often called “The Father of the Republican Party.” In 1902, Grow said that the future of the broad capital ownership idea in the industrial economy—and the end of the struggle between workers and owners—lay in spreading shares in corporations throughout the workforce. Private business was precisely the new capital that needed to become the new homestead.

From 1880 to 1929, a long line of mostly business leaders across the political landscape invented and perfected virtually all the share plans for middle class workers that are used today. Charles Pillsbury developed profit sharing in Minnesota in the nation’s largest flour mill. William Cooper Procter devised ways for workers to acquire company stock using lower-risk cash profit sharing payments and dividends and installments in the Procter & Gamble Ivory Soap empire in Cincinnati. George Eastman in the Rochester high tech miracle of its day, Kodak, likely invented the idea of stock options for every employee that is now ubiquitous from Google to Twitter.

In the ’20s, John D. Rockefeller Jr. created an association of major corporations called the Special Conference Committee in New York City and proposed redesigning capitalism around worker shares of stock and profits which many of the member companies tried to implement. Standard Oil’s exceedingly low-risk employee stock ownership plan became the basis of the Employee Share Purchase Plan now offered to millions of American workers today.

Make no bones about it, the fear of worker movements and socialism played a role in the motives behind many of these plans, but important formats for shares did emerge just the same. Once the government began to tax every individual and corporation in 1913, virtually all of these share plans ended up being encouraged or discouraged by the tax policy flavor of the decade. In the ’50s and ’60s, both Democrats and Republicans supported the idea of profit sharing. Senator Russell Long, Democrat of Louisiana, worked with investment banker and former law professor and economic thinker Louis O. Kelso to make Employee Stock Ownership Plans part of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974. Unfortunately, today—one century later—too few workers have access to meaningful shares in the businesses where they work.

Thomas Piketty’s book, Capital in the Twenty First Century, has been controversial because he raises the issue of a wealth tax to address trends in wealth inequality. While a tax of this magnitude may not be politically viable, it is time for our leaders to develop a hopeful and positive agenda to address the future of the American middle class. What better way than to go back to the American egalitarian tradition of broad-based property ownership of capital in a private market economy? Middle class families have faced relatively flat household incomes for decades and have little access to capital ownership, capital income, and capital gains to expand their wealth.

C-Span Discussion Of Thomas Piketty's "Capitalism" With Elizabeth Warren"

http://paxonbothhouses.blogspot.com/2014/07/warren-buffett-on-coddled-rich.html

Alan: In the C-Span interview above, Warren is brilliant on a number of issues, including the anchor of student debt which is sinking the nation from sea to shining sea. Warren reaches full stride -- indeed demonstrates why she will be president -- when she analyzes America's socio-political system, a system made from our cumulative choices -- and how we have chosen to modify our Democracy in such a way that we deliberately funnel resources into the wallets of the wealthy at the expense of The Middle Class and, by extension, at the expense of our rapidly declining Democracy.Many middle class households face a future of meager retirement savings, difficulty paying for their childrens’ education, and little evidence that an undergraduate college education makes a significant difference in this equation any longer. It is time for new thinking on how to democratize access to capital in ways that remain consistent with our principles. Both progressives and conservatives can turn to their respective icons among America’s leaders to light their way forward.

President James Madison, at the time closely allied with Thomas Jefferson, was not reticent about discussing wealth inequality. He wrote that the property owners of the country were the best protectors of its liberties, and had no doubt that the middle class’s miseries would abate whenever “the laws favor a subdivision of property.” However, Madison did not favor redistribution of wealth. His proposed plan, as spelled out in a 1792 article in the National Gazette, was to “withhold unnecessary opportunities from the few to increase the inequality of property” in order to avoid an “unmerited accumulation of riches.” He wanted laws that, “without violating the rights of property,” would “reduce extreme wealth towards a state of mediocrity”—meaning a robust middle class.

President Ronald Reagan knew this tradition and signed into law many of the strongest pieces of legislation advancing Employee Stock Ownership Plans nationwide, some of which were undone by his successors from both political parties. Reagan called decisively for an Industrial Homestead Act when he said, “I’ve long believed that one of the mainsprings of our own liberty has been the widespread ownership of property among our people … I can’t help but believe that in the future we will see in the United States and throughout the Western world an increasing trend towards the next logical step, employee ownership.”

What might the Founders’ vision of a republic based on broad-property ownership and a thriving middle class look like today?

Using Washington’s cod fishery legislation as a model and Madison’s ideas as a guide, we can explore a restructuring of the tax code to condition any business tax incentive on having some type of share plan for all employees—whether it’s broad-based profit sharing or an Employee Stock Ownership Plan. No business would be required to implement shares, but every business would at least have a serious incentive to consider the idea and decide if it made sense for their organization. Another proposal could involve a tax credit for any corporation that provides broad-based stock options or grants of stock to all of its workers. Silicon Valley would jump at such a proposal.

While these various kinds of shares for employees in businesses are relatively common in the U.S. today, they are not as widespread or as financially significant as would be necessary to meaningfully create more capitalists. Recent Democratic and Republican administrations have pared back many tax incentives for shares without recognizing the larger theme of broad property ownership in American history.

The share approach has the potential to become a powerful bipartisan idea in American political life. It connects to themes of economic and social justice that are important to many liberals. And because shares are a private market economy solution based on real business performance, conservatives may find the idea of creating more capitalists—and more support for capitalism—appealing. Shares present an approach that can advance broad-based property ownership, encourage greater entrepreneurial activity in the workplace, and spread access to wealth—and do it through tax cuts.

While increasing the role of broad-based capitalism in our economy will require courageous political leaders in both parties to start a common conversation—no small feat in today’s climate—it is worthy of serious consideration. We may not have another big idea on economic inequality with so much historical pedigree, bipartisan appeal, and real American tradition out there.

Teddy Roosevelt: “Too much cannot be said against the men of wealth who sacrifice everything to getting wealth. There is not in the world a more ignoble character than the mere money-getting American, insensible to every duty, regardless of every principle, bent only on amassing a fortune, and putting his fortune only to the basest uses —whether these uses be to speculate in stocks and wreck railroads himself, or to allow his son to lead a life of foolish and expensive idleness and gross debauchery, or to purchase some scoundrel of high social position, foreign or native, for his daughter. Such a man is only the more dangerous if he occasionally does some deed like founding a college or endowing a church, which makes those good people who are also foolish forget his real iniquity. These men are equally careless of the working men, whom they oppress, and of the State, whose existence they imperil. There are not very many of them, but there is a very great number of men who approach more or less closely to the type, and, just in so far as they do so approach, they are curses to the country." Theodore Roosevelt - February, 1895 - http://books.google.com/books?id=2wIoAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA9&lpg=PA9&dq=%E2%80%9CToo+much+cannot+be+said+against+the+men+of+wealth+who+sacrifice+everything+to+getting+wealth.+%22&source=bl&ots=tlzVCZMAuz&sig=DZ9KUKiPiBTUlThoSVs6KzQTvF4&hl=en&ei=OxibTcHrCIGdgQev_o2eBw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CBsQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=%E2%80%9CToo%20much%20cannot%20be%20said%20against%20the%20men%20of%20wealth%20who%20sacrifice%20everything%20to%20getting%20wealth.%20%22&f=false

More Teddy Roosevelt Quotes

Abraham Lincoln: "In my present position I could scarcely be justified were I to omit raising a warning voice against this approach of returning despotism. It is not needed nor fitting here that a general argument should be made in favor of popular institutions, but there is one point, with its connections, not so hackneyed as most others, to which I ask a brief attention. It is the effort to place capital on an equal footing with, if not above, labor in the structure of government. It is assumed that labor is available only in connection with capital; that nobody labors unless somebody else, owning capital, somehow by the use of it induces him to labor. This assumed, it is next considered whether it is best that capital shall hire laborers, and thus induce them to work by their own consent, or buy them and drive them to it without their consent. Having proceeded so far, it is naturally concluded that all laborers are either hired laborers or what we call slaves. And further, it is assumed that whoever is once a hired laborer is fixed in that condition for life. Now there is no such relation between capital and labor as assumed, nor is there any such thing as a free man being fixed for life in the condition of a hired laborer. Both these assumptions are false, and all inferences from them are groundless. Labor is prior to and independent of capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration." Read more: State of the Union Address: Abraham Lincoln (December 3, 1861) Infoplease.com http://www.infoplease.com/t/hist/state-of-the-union/73.html#ixzz17XlRsbev

More Abe Lincoln Quotes

"What Abraham Lincoln Had To Say About Occupy Wall Street"

***

"Geese are but Geese tho' we may think 'em Swans;

and Truth will be Truth tho' it sometimes prove mortifying and distasteful."

Benjamin Franklin to Robert Morris - 25 December, 1783

"The Remissness of our People in Paying Taxes is highly blameable; the Unwillingness to pay them is still more so. I see, in some Resolutions of Town Meetings, a Remonstrance against giving Congress a Power to take, as they call it, the People's Money out of their Pockets, tho' only to pay the Interest and Principal of Debts duly contracted. They seem to mistake the Point. Money, justly due from the People, is their Creditors' Money, and no longer the Money of the People, who, if they withold it, should be compell'd to pay by some Law.

All Property, indeed, except the Savage's temporary Cabin, his Bow, his Matchcoat, and other little Acquisitions, absolutely necessary for his Subsistence, seems to me to be the Creature of public Convention. Hence the Public has the Right of Regulating Descents, and all other Conveyances of Property, and even of limiting the Quantity and the Uses of it. All the Property that is necessary to a Man, for the Conservation of the Individual and the Propagation of the Species, is his natural Right, which none can justly deprive him of: But all Property superfluous to such purposes is the Property of the Publick, who, by their Laws, have created it, and who may therefore by other Laws dispose of it, whenever the Welfare of the Publick shall demand such Disposition. He that does not like civil Society on these Terms, let him retire and live among Savages. He can have no right to the benefits of Society, who will not pay his Club towards the Support of it."

More Ben Franklin Quotes

***

Reagan Budget Director, David Stockman, who oversaw the biggest tax cut in the history of humankind: “In 1985, the top five percent of the households – the wealthiest five percent – had net worth of $8 trillion – which is a lot. Today, after serial bubble after serial bubble, the top five per cent have net worth of $40 trillion. The top five percent have gained more wealth than the whole human race had created prior to 1980.” Elsewhere in this same CBS “60 Minutes” interview, Mr. Stockman describes America's obsession with tax cuts as "religion, something embedded in the catechism," "rank demagoguery, we should call it what it is," and "We've demonized taxes. We've created... the idea that they're a metaphysical evil." And finally, this encompassing observation: "The Republican Party, as much as it pains me to say this, should be ashamed of themselves." - http://www.cbsnews.com/video/watch/?id=7009217n&tag=contentMain;contentAux /// http://finance.yahoo.com/tech-ticker/obama-gop-agree-to-tax-breaks-but-%22we-need-major-tax-increases%22-david-stockman-says-535688.html?tickers=^DJI,^GSPC,GLD,DIA,TBT,TLT,UUP /// http://finance.yahoo.com/tech-ticker/david-stockman-lack-of-middle-class-jobs-low-growth-alleged-recovery-yftt_535691.html /// http://www.cbsnews.com/video/watch/?id=7009246n&tag=contentBody;housing (There is a self-resolving glitch near the beginning of this final clip.)

Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s famous “class warfare” speech.

Madison Square Garden. October 31, 1936.

More Franklin Delano Roosevelt Quotes

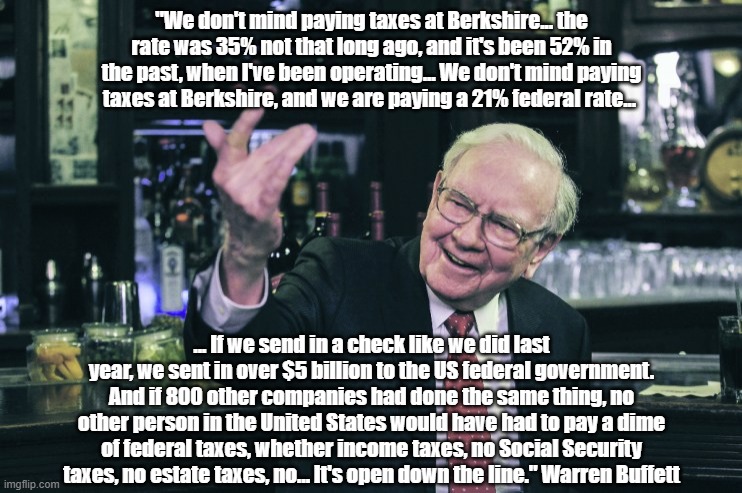

Warren Buffett Interviewed By Tom Brokaw

***

"I will believe that corporations are people when Texas executes one."

***

"Once Upon A Time... Hidden History Of Corporations In The United States"

"Viral Video Examines Gap Between The Super Rich And Everyone Else. (Great Graphics!)"

G.K. Chesterton - The Anarchy of the Rich

"Inside Job"

Oscar winning documentary on Wall Street malfeasance

Freely streamable online (with Spanish subtitles)

"This Is Why They Hate You And Want You To Die"

"99 Must-Reads On Income Inequality"

***

Capitalism

(most particularly unregulated "Cowboy Capitalism" - and its yahoos)

Capitalism: A 2023 Compendium Of Best "Pax-Barbaria" Posts

Billionaire Nick Hanauer's TED Talk: "Capitalism's Dirty Little Secret"

C-Span Discussion Of Thomas Piketty's "Capitalism" With Elizabeth Warren"

http://paxonbothhouses.blogspot.com/2014/07/c-span-discussion-of-thomas-pikettys.htmlAlan: In the C-Span interview above, Warren is brilliant on a number of issues, including the anchor of student debt sinking the nation from sea to shining sea. Warren reaches full stride -- indeed demonstrates why she will be president -- when she analyzes America's socio-political system, a system made from our cumulative choices -- and how we have chosen to modify our Democracy in such a way that we deliberately funnel resources into the wallets of the wealthy at the expense of The Middle Class and, by extension, at the expense of our rapidly declining Democracy.

***

"The work of heaven alone is material; the making of a material world.

The work of hell is entirely spiritual."

G.K. Chesterton

***

"Politics, Economics And The 101 Courses You Wish You Had"

***

Alan: Another approach to remedying income inequality would be to lower a corporation's tax rate in direct relationship to the number of new jobs each corporation creates over the course of a fiscal year. If a corporation is not creating new jobs, or if it is eliminating jobs due to automation, robotization and software enhancement, it would not be treated as favorably as those corporations that are actively adding new jobs. The tax advantage accruing from the creation of new jobs could be made so advantageous that corporations might choose to create "unnecessary" jobs (perhaps in research or "community outreach") for the sole purpose of securing tax rate reduction. The goal, as I see it, is threefold: 1.) to foster growth, 2.) to create jobs and 3.) to redistribute wealth through the creation of jobs.

A related phenomenon...

Several decades ago, when Japanese engineers started producing automobiles demonstrably superior to their Detroit counterparts, millions of Americans banded together to boycott the purchase of Japanese cars in favor of vehicles "Made in America." Today, similar opprobrium should be accorded any American company that re-incorporates offshore. Congress could even impose tariffs on goods and services supplied by such companies. Since foreign brands have no choice about overseas incorporation, it is appropriate that turncoat American corporations be shunned while foreign brands are welcomed. American companies which turn their back on The United States flirt with traitorous betrayal and should be punished for their cut-throat pragmatism, regardless its "legality."

*****

Hidden History of Corporations in the United States

When American colonists declared independence from England in 1776, they also freed themselves from control by English corporations that extracted their wealth and dominated trade. After fighting a revolution to end this exploitation, our country’s founders retained a healthy fear of corporate power and wisely limited corporations exclusively to a business role. Corporations were forbidden from attempting to influence elections, public policy, and other realms of civic society.

Initially, the privilege of incorporation was granted selectively to enable activities that benefited the public, such as construction of roads or canals. Enabling shareholders to profit was seen as a means to that end. The states also imposed conditions (some of which remain on the books, though unused) like these*:

- Corporate charters (licenses to exist) were granted for a limited time and could be revoked promptly for violating laws.

- Corporations could engage only in activities necessary to fulfill their chartered purpose.

- Corporations could not own stock in other corporations nor own any property that was not essential to fulfilling their chartered purpose.

- Corporations were often terminated if they exceeded their authority or caused public harm.

- Owners and managers were responsible for criminal acts committed on the job.

- Corporations could not make any political or charitable contributions nor spend money to influence law-making.

For 100 years after the American Revolution, legislators maintained tight controll of the corporate chartering process. Because of widespread public opposition, early legislators granted very few corporate charters, and only after debate. Citizens governed corporations by detailing operating conditions not just in charters but also in state constitutions and state laws. Incorporated businesses were prohibited from taking any action that legislators did not specifically allow.

States also limited corporate charters to a set number of years. Unless a legislature renewed an expiring charter, the corporation was dissolved and its assets were divided among shareholders. Citizen authority clauses limited capitalization, debts, land holdings, and sometimes, even profits. They required a company’s accounting books to be turned over to a legislature upon request. The power of large shareholders was limited by scaled voting, so that large and small investors had equal voting rights. Interlocking directorates were outlawed. Shareholders had the right to remove directors at will.

In Europe, charters protected directors and stockholders from liability for debts and harms caused by their corporations. American legislators explicitly rejected this corporate shield. The penalty for abuse or misuse of the charter was not a plea bargain and a fine, but dissolution of the corporation.

In 1819 the U.S. Supreme Court tried to strip states of this sovereign right by overruling a lower court’s decision that allowed New Hampshire to revoke a charter granted to Dartmouth College by King George III. The Court claimed that since the charter contained no revocation clause, it could not be withdrawn. The Supreme Court’s attack on state sovereignty outraged citizens. Laws were written or re-written and new state constitutional amendments passed to circumvent the (

Dartmouth College v Woodward) ruling. Over several decades starting in 1844, nineteen states amended their constitutions to make corporate charters subject to alteration or revocation by their legislatures. As late as 1855 it seemed that the Supreme Court had gotten the people’s message when in

Dodge v. Woolsey it reaffirmed state’s powers over “artificial bodies.”

But the men running corporations pressed on. Contests over charter were battles to control labor, resources, community rights, and political sovereignty. More and more frequently, corporations were abusing their charters to become conglomerates and trusts. They converted the nation’s resources and treasures into private fortunes, creating factory systems and company towns. Political power began flowing to absentee owners, rather than community-rooted enterprises.

The industrial age forced a nation of farmers to become wage earners, and they became fearful of unemployment–a new fear that corporations quickly learned to exploit. Company towns arose. and blacklists of labor organizers and workers who spoke up for their rights became common. When workers began to organize, industrialists and bankers hired private armies to keep them in line. They bought newspapers to paint businessmen as heroes and shape public opinion. Corporations bought state legislators, then announced legislators were corrupt and said that they used too much of the public’s resources to scrutinize every charter application and corporate operation.

Government spending during the Civil War brought these corporations fantastic wealth. Corporate executives paid “borers” to infest Congress and state capitals, bribing elected and appointed officials alike. They pried loose an avalanche of government financial largesse. During this time, legislators were persuaded to give corporations limited liability, decreased citizen authority over them, and extended durations of charters.

Attempts were made to keep strong charter laws in place, but with the courts applying legal doctrines that made protection of corporations and corporate property the center of constitutional law, citizen sovereignty was undermined. As corporations grew stronger, government and the courts became easier prey. They freely reinterpreted the U.S. Constitution and transformed common law doctrines.

From that point on, the 14th Amendment, enacted to protect rights of freed slaves, was used routinely to grant corporations constitutional “personhood.” Justices have since struck down hundreds of local, state and federal laws enacted to protect people from corporate harm based on this illegitimate premise. Armed with these “rights,” corporations increased control over resources, jobs, commerce, politicians, even judges and the law.

A United States Congressional committee concluded in 1941, “The principal instrument of the concentration of economic power and wealth has been the corporate charter with unlimited power….”

Many U.S.-based corporations are now transnational, but the corrupted charter remains the legal basis for their existence. At Reclaim Democracy!, we believe citizens can reassert the convictions of our nation’s founders who struggled successfully to free us from corporate rule in the past. These changes must occur at the most fundamental level — the U.S. Constitution.

- Taking Care of Business: Citizenship and the Charter of Incorporation by Richard L. Grossman and Frank T. Adams (published by POCLAD) was a primary source

- The Transformation of American Law, Volume I & Volume II by Morton J. Horwitz

Please visit our Corporate Personhood page for a huge library of articles exploring this topic more deeply. You might also be interested to read outproposed Constitutional Amendments to revoke Illegitimate corporate power, erode the power of money over elections, and establish an affirmative constitutional right to vote.

No comments:

Post a Comment