Cosmic Consciousness: Maurice Bucke’s Pioneering 19th-Century Theory of Transcendence and the Six Steps of Illumination

“Our normal waking consciousness,” William James wrote in 1902, “is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different… No account of the universe in its totality can be final which leaves these other forms of consciousness quite disregarded.”

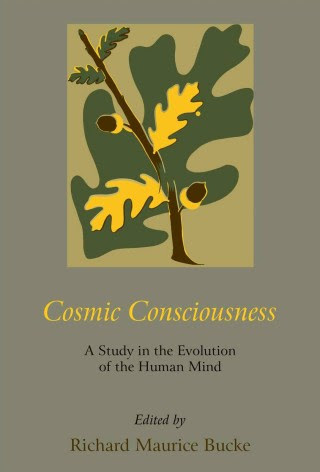

A year earlier, the Canadian psychiatrist and adventurer Maurice Bucke (March 18, 1837–February 19, 1902) published a stunning personal account and psychological study of a dazzling form of consciousness that lies just on the other side of that filmiest of screens, accessible to all. Bucke’s Cosmic Consciousness: A Study in the Evolution of the Human Mind (public library) went on to influence generations of thinkers as diverse as Albert Einstein, Erich Fromm, Abraham Maslow, Alan Watts, and Steve Jobs.

Maurice Bucke

By his own account, Bucke was “born of good middle class English stock,” but grew up almost entirely without education, working tirelessly on his parents’ farm in the backwoods of Canada — tending cattle, horses, sheep, and pigs, working in the hay field, driving oxen and horses, and running various errands from the earliest age. He learned to read when he was still a small child and soon began devouring novels and poetry. He remembers that, like Emily Dickinson, he “never, even as a child, accepted the doctrines of the Christian church” — a disposition utterly countercultural in that era of extreme religiosity.

Although his mother died when he was very young and his father shortly thereafter, Bucke recalls being often overcome by “a sort of ecstasy of curiosity and hope.” (What a lovely phrase.) At sixteen, he left the farm “to live or die as might happen,” trekking from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico, from Ohio to San Francisco, working on farms and railroads and steamboats, narrowly escaping death by illness, starvation, and battle on several occasions. In his twentieth year, he heard of the first major discovery of silver ore in America and joined a mining party, of which he was the only survivor, and barely: On his way to California, while crossing the mountains of the Sierra Nevada, he suffered frostbite so severe that one foot and a few toes on the remaining foot had to be amputated.

When he finally made it to the Pacific Coast, Bucke used a moderate inheritance from his mother to give himself a proper college education. He devoured ideas from books as wide-ranging as On the Origin of Species and Shelley’s poems. After graduating, he taught himself French so that he could read Auguste Comte and German so that he could read Goethe. At thirty, he discovered and became instantly besotted with Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, which he felt contained vaster truth and richer meaning than any book he had previously encountered. It was Whitman who catalyzed Bucke’s transcendent experience.

Art by Margaret C. Cook from a rare 1913 edition of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. (Available as a print.)

More than a century before Michael Pollan insisted in his masterly inquiry into the science of psychedelics that “the Beyond, whatever it consists of, might not be nearly as far away or inaccessible as we think,” Bucke suggests that it might be just a poem away. Writing in the third person, as was customary for “the writer” in the nineteenth century, he recounts his transformative illumination:

It was in the early spring, at the beginning of his thirty-sixth year. He and two friends had spent the evening reading Wordsworth, Shelley, Keats, Browning, and especially Whitman. They parted at midnight, and he had a long drive in a hansom (it was in an English city). His mind, deeply under the influence of the ideas, images and emotions called up by the reading and talk of the evening, was calm and peaceful. He was in a state of quiet, almost passive enjoyment. All at once, without warning of any kind, he found himself wrapped around as it were by a flame-colored cloud. For an instant he thought of fire, some sudden conflagration in the great city; the next, he knew that the light was within himself. Directly afterwards came upon him a sense of exultation, of immense joyousness accompanied or immediately followed by an intellectual illumination quite impossible to describe. Into his brain streamed one momentary lightning-flash of the Brahmic Splendor which has ever since lightened his life; upon his heart fell one drop of Brahmic Bliss, leaving thenceforward for always an aftertaste of heaven. Among other things he did not come to believe, he saw and knew that the Cosmos is not dead matter but a living Presence, that the soul of man is immortal, that the universe is so built and ordered that without any peradventure all things work together for the good of each and all, that the foundation principle of the world is what we call love and that the happiness of every one is in the long run absolutely certain.

Although the illumination only lasted a moment, Burke felt that he learned more in those few seconds than in all his years of study, more even than what could ever possibly be taught by the standard modes of scholarship. (“The transformation of the heart is a wondrous thing, no matter how you land there,” Patti Smith would write a century later.) In that instant, as “the secret of Whitman’s transcendent greatness was revealed,” he experienced something he could never forget, which he called “cosmic consciousness” — a term he borrowed from the English philosopher and poet Edward Carpenter, who was among the first Western thinkers to popularize the ancient teachings of the Eastern philosophical and spiritual traditions.

Bucke identifies three layers of consciousness, each built upon the lower: Simple Consciousness — a basic awareness, which most non-human animals also possess; Self-Consciousness, which render one aware not only of trees, rivers, and one’s own body, but also of oneself as “a distinct entity apart from all the rest of the universe,” capable of treating one’s own thoughts and feelings as objects of consciousness itself; and Cosmic Consciousness, which Bucke defines as an awareness of “the life and order of the universe.” In a passage of striking consonance with William James’s framework of transcendent experiences, he writes:

Along with the consciousness of the cosmos there occurs an intellectual enlightenment or illumination which alone would place the individual on a new plane of existence — would make him almost a member of a new species. To this is added a state of moral exaltation, an indescribable feeling of elevation, elation, and joyousness, and a quickening of the moral sense, which is fully as striking and more important both to the individual and to the race than is the enhanced intellectual power. With these come, what may be called a sense of immortality, a consciousness of eternal life, not a conviction that he shall have this, but the consciousness that he has it already.

In language that closely parallels the way people describe the effects of psychedelics, Bucke limns the nature and sequence of this revelatory experience:

Like a flash there is presented to [the person’s] consciousness a clear conception (a vision) in outline of the meaning and drift of the universe. He does not come to believe merely; but he sees and knows that the cosmos, which to the self conscious mind seems made up of dead matter, is in fact far otherwise — is in very truth a living presence. He sees that instead of men being, as it were, patches of life scattered through an infinite sea of non-living substance, they are in reality specks of relative death in an infinite ocean of life.

[…]

The person who passes through this experience will learn in the few minutes, or even moments, of its continuance more than in months or years of study, and he will learn much that no study ever taught or can teach. Especially does he obtain such a conception of THE WHOLE, or at least of an immense WHOLE, as dwarfs all conception, imagination or speculation, springing from and belonging to ordinary self consciousness, such a conception as makes the old attempts to mentally grasp the universe and its meaning petty and even ridiculous.

A year before William James published his classic treatise on consciousness and the four features of transcendent experiences, Bucke — whom James references — outlines the characteristics of cosmic consciousness, at the heart of which he places the Eastern concept of “Brahmic Splendor,” also reflected in Dante’s transhumanized state in Paradisio.

- A sudden appearance, often accompanied by immersion in a cloud of haze or fire. “The instantaneousness of the illumination,” Bucke writes, “is one of its most striking features. It can be compared with nothing so well as with a dazzling flash of lightning in a dark night, bringing the landscape which had been hidden into clear view.” (A century later, physicist Freeman Dyson would describe one of his most significant scientific breakthroughs as “a flash of illumination.”)

- An ecstatic surge of emotion — “joy, assurance, triumph, ‘salvation'” — transcending “the pleasures and pains, loves and hates, joys and sorrows,peace and war, life and death, of self conscious man.”

- An intellectual illumination, arising from the emotional ecstasy, difficult to put into words. (William James also lists ineffability as the foremost feature of transcendent experiences.)

- Dissolution of the fear of death.

- Dissolution of the sense of sin or wrongness.

- A sense of immortality accompanying the moral elevation. “This is not an intellectual conviction, such as comes with the solution of a problem, nor is it an experience such as learning something unknown before,” Bucke writes. “It is far more simple and elementary.”

Of central importance in this experience of illumination, he argues, are the character — “intellectual, moral and physical” — and age of the person undergoing it. The illumination is truer and richer, Bucke suggest, when experienced at a later age:

Should we hear of a case of cosmic consciousness occurring at twenty, for instance, we should at first doubt the truth of the account, and if forced to believe it we should expect the man (if he lived) to prove himself, in some way, a veritable spiritual giant.

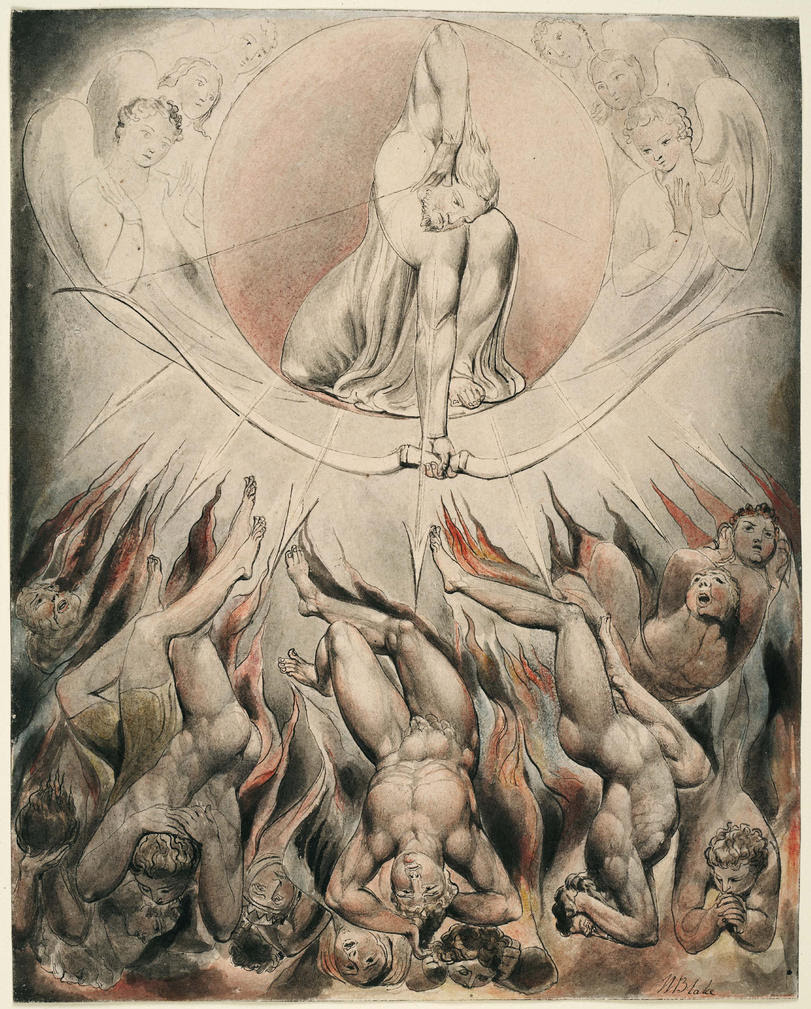

Art by William Blake for a rare 1808 edition of Milton’s Paradise Lost

Drawing on the memoirs, biographies, and letters of historical figures, he goes on to compose a kind of ledger of such spiritual giants who have reported experiences indicative of cosmic consciousness, noting next to each person the age at which they underwent the illumination. Among them he lists:

- Francis Bacon (30)

- William Blake (31)

- Blaise Pascal (31)

- Honoré de Balzac (32)

- Walt Whitman (34)

- Gautama Buddha (35)

- Edward Carpenter (37)

- Baruch Spinoza (45)

Bucke sees the attainment of cosmic consciousness as a vital step in the spiritual and moral evolution of our species, but he takes care to emphasize that it “must not be looked upon as being in any sense supernatural or supranormal — as anything more or less than a natural growth.” With electric exuberance, he channels his optimism, both prescient and bittersweet in the hindsight of history:

The immediate future of our race… is indescribably hopeful. There are at the present moment impending over us three revolutions, the least of which would dwarf the ordinary historic upheaval called by that name into absolute insignificance. They are: (1) The material,economic and social revolution which will depend upon and result from the establishment of aerial navigation. (2) The economic and social revolution which will abolish individual ownership and rid the earth at once of two immense evils — riches and poverty. And (3) The psychical revolution of which there is here question.

Either of the first two would (and will) radically change the conditions of, and greatly uplift, human life; but the third will do more for humanity than both of the former, were their importance multiplied by hundreds or even thousands.

The three operating (as they will) together will literally create a new heaven and a new earth. Old things will be done away and all will become new.

Art by William Blake for a rare 1808 edition of Milton’s Paradise Lost

The net result, Bucke envisions, will be nothing less than a revolution of the human soul. While human beings will remain resolutely spiritual, this revolution would be predicated on the dissolution of organized religion:

Religion will… not depend on tradition. It will not be believed and disbelieved. It will not be a part of life,belonging to certain hours, times, occasions. It will not be in sacred books nor in the mouths of priests. It will not dwell in churches and meetings and forms and days. Its life will not be in prayers,hymns nor discourses. It will not depend on special revelations, on the words of gods who came down to teach, nor on any bible or bibles. It will have no mission to save men from their sins or to secure them entrance to heaven. It will not teach a future immortality nor future glories, for immortality and all glory will exist in the here and now. The evidence of immortality will live in every heart as sight in every eye.

Complement Bucke’s Cosmic Consciousness with Virginia Woolf’s ecstatic description of a psychedelic experience, physicist Alan Lightman’s poetic account of a secular transcendent experience, and neuroscientist Christof Koch on the central mystery of consciousness, then revisit Edward Carpenter, who inspired Bucke’s ideas, on love, pain, and growth.

No comments:

Post a Comment