“To decide whether life is worth living is to answer the fundamental question of philosophy,” Albert Camus wrote in his classic 119-page essay The Myth of Sisyphus in 1942. “Everything else… is child’s play; we must first of all answer the question.”

Sometimes, life asks this question not as a thought experiment but as a gauntlet hurled with the raw brutality of living.

That selfsame year, the young Viennese neurologist and psychiatrist Viktor Frankl (March 26, 1905–September 2, 1997) was taken to Auschwitz along with more than a million human beings robbed of the basic right to answer this question for themselves, instead deemed unworthy of living. Some survived by reading. Some through humor. Some by pure chance. Most did not. Frankl lost his mother, his father, and his brother to the mass murder in the concentration camps. His own life was spared by the tightly braided lifeline of chance, choice, and character.

Viktor Frankl

A mere eleven months after surviving the unsurvivable, Frankl took up the elemental question at the heart of Camus’s philosophical parable in a set of lectures, which he himself edited into a slim, potent book published in Germany in 1946, just as he was completing Man’s Search for Meaning.

As our collective memory always tends toward amnesia and erasure — especially of periods scarred by civilizational shame — these existential infusions of sanity and lucid buoyancy fell out of print and were soon forgotten. Eventually rediscovered — as is also the tendency of our collective memory when the present fails us and we must lean for succor on the life-tested wisdom of the past — they are now published in English for the first time as Yes to Life: In Spite of Everything (public library).

Frankl begins by considering the question of whether life is worth living through the central fact of human dignity. Noting how gravely the Holocaust disillusioned humanity with itself, he cautions against the defeatist “end-of-the-world” mindset with which many responded to this disillusionment, but cautions equally against the “blithe optimism” of previous, more naïve eras that had not yet faced this gruesome civilizational mirror reflecting what human beings are capable of doing to one another. Both dispositions, he argues, stem from nihilism. In consonance with his colleague and contemporary Erich Fromm’s insistence that we can only transcend the shared laziness of optimism and pessimism through rational faith in the human spirit, Frankl writes:

We cannot move toward any spiritual reconstruction with a sense of fatalism such as this.

We cannot move toward any spiritual reconstruction with a sense of fatalism such as this.

Liminal Worlds by Maria Popova. (Available as a print.)

Generations and myriad cultural upheavals before Zadie Smith observed that “progress is never permanent, will always be threatened, must be redoubled, restated and reimagined if it is to survive,” Frankl considers what “progress” even means, emphasizing the centrality of our individual choices in its constant revision:

Today every impulse for action is generated by the knowledge that there is no form of progress on which we can trustingly rely. If today we cannot sit idly by, it is precisely because each and every one of us determines what and how far something “progresses.” In this, we are aware that inner progress is only actually possible for each individual, while mass progress at most consists of technical progress, which only impresses us because we live in a technical age.

Today every impulse for action is generated by the knowledge that there is no form of progress on which we can trustingly rely. If today we cannot sit idly by, it is precisely because each and every one of us determines what and how far something “progresses.” In this, we are aware that inner progress is only actually possible for each individual, while mass progress at most consists of technical progress, which only impresses us because we live in a technical age.

Insisting that it takes a measure of moral strength not to succumb to nihilism, be it that of the pessimist or of the optimist, he exclaims:

Give me a sober activism anytime, rather than that rose-tinted fatalism!

Give me a sober activism anytime, rather than that rose-tinted fatalism!

How steadfast would a person’s belief in the meaningfulness of life have to be, so as not to be shattered by such skepticism. How unconditionally do we have to believe in the meaning and value of human existence, if this belief is able to take up and bear this skepticism and pessimism?

[…]

Through this nihilism, through the pessimism and skepticism, through the soberness of a “new objectivity” that is no longer that “new” but has grown old, we must strive toward a new humanity.

Sophie Scholl, upon whom chance did not smile as favorably as it did upon Frankl, affirmed this notion with her insistence that living with integrity and belief in human goodness is the wellspring of courage as she courageously faced her own untimely death in the hands of the Nazis. But while the Holocaust indisputably disenchanted humanity, Frankl argues, it also indisputably demonstrated “that what is human is still valid… that it is all a question of the individual human being.” Looking back on the brutality of the camps, he reflects:

What remained was the individual person, the human being — and nothing else. Everything had fallen away from him during those years: money, power, fame; nothing was certain for him anymore: not life, not health, not happiness; all had been called into question for him: vanity, ambition, relationships. Everything was reduced to bare existence. Burnt through with pain, everything that was not essential was melted down — the human being reduced to what he was in the last analysis: either a member of the masses, therefore no one real, so really no one — the anonymous one, a nameless thing (!), that “he” had now become, just a prisoner number; or else he melted right down to his essential self.

What remained was the individual person, the human being — and nothing else. Everything had fallen away from him during those years: money, power, fame; nothing was certain for him anymore: not life, not health, not happiness; all had been called into question for him: vanity, ambition, relationships. Everything was reduced to bare existence. Burnt through with pain, everything that was not essential was melted down — the human being reduced to what he was in the last analysis: either a member of the masses, therefore no one real, so really no one — the anonymous one, a nameless thing (!), that “he” had now become, just a prisoner number; or else he melted right down to his essential self.

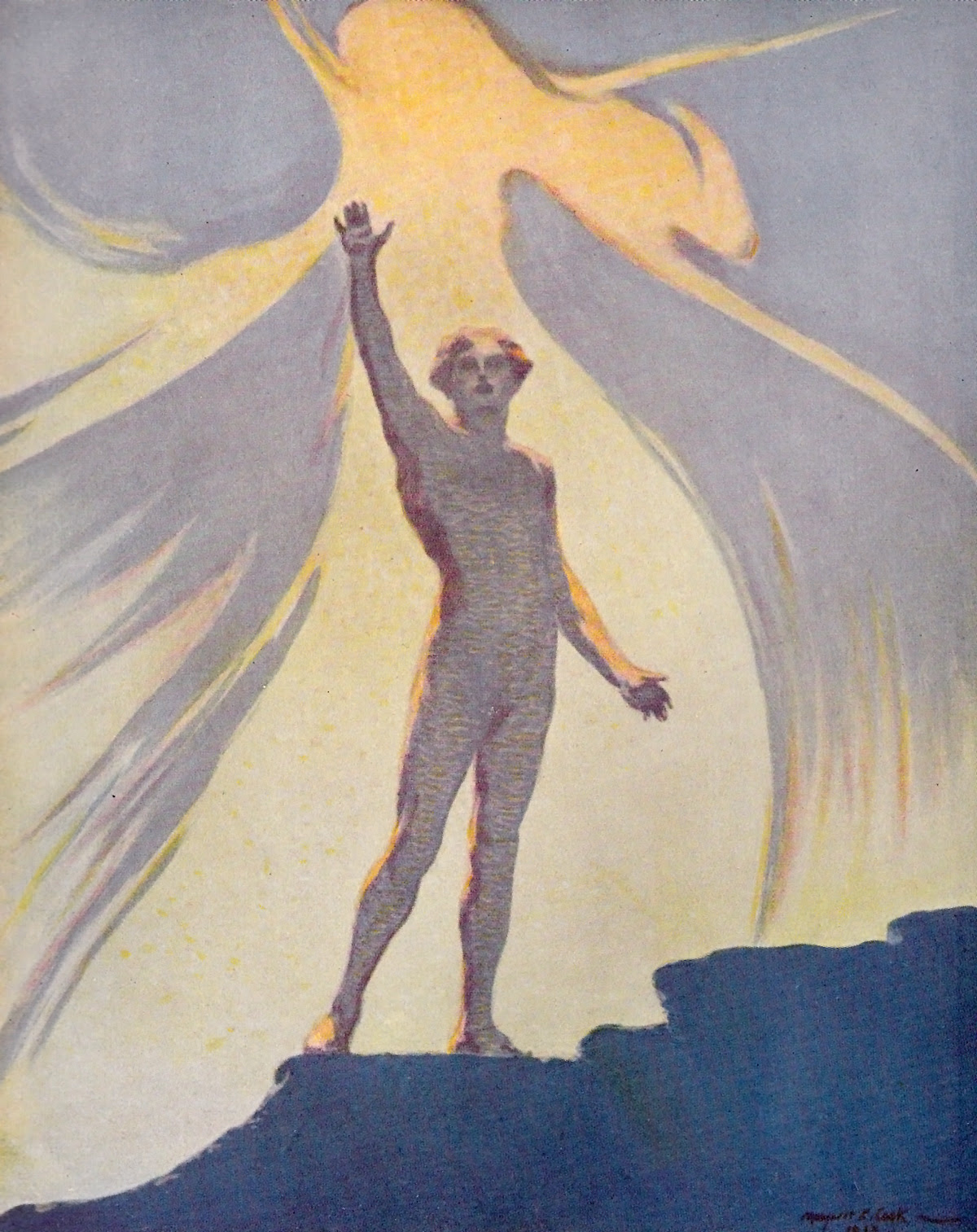

Illustration by Margaret C. Cook for a rare 1913 edition of Leaves of Grass. (Available as a print.)

In a sentiment that bellows from the hallways of history into the great vaulted temple of timeless truth, he adds:

Everything depends on the individual human being, regardless of how small a number of like-minded people there is, and everything depends on each person, through action and not mere words, creatively making the meaning of life a reality in his or her own being.

Everything depends on the individual human being, regardless of how small a number of like-minded people there is, and everything depends on each person, through action and not mere words, creatively making the meaning of life a reality in his or her own being.

Frankl then turns to the question of finding a sense of meaning when the world gives us ample reasons to view life as meaningless — the question of “continuing to live despite persistent world-weariness.” Writing in the post-war pre-dawn of the golden age of consumerism, which has built a global economy by continually robbing us of the sense of meaning and selling it back to us at the price of the product, Frankl first dismantles the notion that meaning is to be found in the pursuit and acquisition of various pleasures:

Let us imagine a man who has been sentenced to death and, a few hours before his execution, has been told he is free to decide on the menu for his last meal. The guard comes into his cell and asks him what he wants to eat, offers him all kinds of delicacies; but the man rejects all his suggestions. He thinks to himself that it is quite irrelevant whether he stuffs good food into the stomach of his organism or not, as in a few hours it will be a corpse. And even the feelings of pleasure that could still be felt in the organism’s cerebral ganglia seem pointless in view of the fact that in two hours they will be destroyed forever. But the whole of life stands in the face of death, and if this man had been right, then our whole lives would also be meaningless, were we only to strive for pleasure and nothing else — preferably the most pleasure and the highest degree of pleasure possible. Pleasure in itself cannot give our existence meaning; thus the lack of pleasure cannot take away meaning from life, which now seems obvious to us.

Let us imagine a man who has been sentenced to death and, a few hours before his execution, has been told he is free to decide on the menu for his last meal. The guard comes into his cell and asks him what he wants to eat, offers him all kinds of delicacies; but the man rejects all his suggestions. He thinks to himself that it is quite irrelevant whether he stuffs good food into the stomach of his organism or not, as in a few hours it will be a corpse. And even the feelings of pleasure that could still be felt in the organism’s cerebral ganglia seem pointless in view of the fact that in two hours they will be destroyed forever. But the whole of life stands in the face of death, and if this man had been right, then our whole lives would also be meaningless, were we only to strive for pleasure and nothing else — preferably the most pleasure and the highest degree of pleasure possible. Pleasure in itself cannot give our existence meaning; thus the lack of pleasure cannot take away meaning from life, which now seems obvious to us.

He quotes a short verse by the great Indian poet and philosopher Rabindranath Tagore — the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize, Einstein’s onetime conversation partner in contemplating science and spirituality, and a man who thought deeply about human nature:

I slept and dreamt

I slept and dreamt

that life was joy.

I awoke and saw

that life was duty.

I worked — and behold,

duty was joy.

In consonance with Camus’s view of happiness as a moral obligation — an outcome to be attained not through direct pursuit but as a byproduct of living with authenticity and integrity — Frankl reflects on Tagore’s poetic point:

So, life is somehow duty, a single, huge obligation. And there is certainly joy in life too, but it cannot be pursued, cannot be “willed into being” as joy; rather, it must arise spontaneously, and in fact, it does arise spontaneously, just as an outcome may arise: Happiness should not, must not, and can never be a goal, but only an outcome; the outcome of the fulfillment of that which in Tagore’s poem is called duty… All human striving for happiness, in this sense, is doomed to failure as luck can only fall into one’s lap but can never be hunted down.

So, life is somehow duty, a single, huge obligation. And there is certainly joy in life too, but it cannot be pursued, cannot be “willed into being” as joy; rather, it must arise spontaneously, and in fact, it does arise spontaneously, just as an outcome may arise: Happiness should not, must not, and can never be a goal, but only an outcome; the outcome of the fulfillment of that which in Tagore’s poem is called duty… All human striving for happiness, in this sense, is doomed to failure as luck can only fall into one’s lap but can never be hunted down.

In a sentiment James Baldwin would echo two decades later in his superb forgotten essay on the antidote to the hour of despair and life as a moral obligation to the universe, Frankl turns the question unto itself:

At this point it would be helpful [to perform] a conceptual turn through 180 degrees, after which the question can no longer be “What can I expect from life?” but can now only be “What does life expect of me?” What task in life is waiting for me?

At this point it would be helpful [to perform] a conceptual turn through 180 degrees, after which the question can no longer be “What can I expect from life?” but can now only be “What does life expect of me?” What task in life is waiting for me?

Now we also understand how, in the final analysis, the question of the meaning of life is not asked in the right way, if asked in the way it is generally asked: it is not we who are permitted to ask about the meaning of life — it is life that asks the questions, directs questions at us… We are the ones who must answer, must give answers to the constant, hourly question of life, to the essential “life questions.” Living itself means nothing other than being questioned; our whole act of being is nothing more than responding to — of being responsible toward — life. With this mental standpoint nothing can scare us anymore, no future, no apparent lack of a future. Because now the present is everything as it holds the eternally new question of life for us.

Another of Margaret C. Cook’s illustrations for the 1913 English edition of Leaves of Grass. (Available as a print.)

Frankl adds a caveat of tremendous importance — triply so in our present culture of self-appointed gurus, self-help demagogues, and endless podcast feeds of interviews with accomplished individuals attempting to distill a universal recipe for self-actualization:

The question life asks us, and in answering which we can realize the meaning of the present moment, does not only change from hour to hour but also changes from person to person: the question is entirely different in each moment for every individual.

The question life asks us, and in answering which we can realize the meaning of the present moment, does not only change from hour to hour but also changes from person to person: the question is entirely different in each moment for every individual.

We can, therefore, see how the question as to the meaning of life is posed too simply, unless it is posed with complete specificity, in the concreteness of the here and now. To ask about “the meaning of life” in this way seems just as naive to us as the question of a reporter interviewing a world chess champion and asking, “And now, Master, please tell me: which chess move do you think is the best?” Is there a move, a particular move, that could be good, or even the best, beyond a very specific, concrete game situation, a specific configuration of the pieces?

What emerges from Frankl’s inversion of the question is the sense that, just as learning to die is learning to meet the universe on its own terms, learning to live is learning to meet the universe on its own terms — terms that change daily, hourly, by the moment:

One way or another, there can only be one alternative at a time to give meaning to life, meaning to the moment — so at any time we only need to make one decision about how we must answer, but, each time, a very specific question is being asked of us by life. From all this follows that life always offers us a possibility for the fulfillment of meaning, therefore there is always the option that it has a meaning. One could also say that our human existence can be made meaningful “to the very last breath”; as long as we have breath, as long as we are still conscious, we are each responsible for answering life’s questions.

One way or another, there can only be one alternative at a time to give meaning to life, meaning to the moment — so at any time we only need to make one decision about how we must answer, but, each time, a very specific question is being asked of us by life. From all this follows that life always offers us a possibility for the fulfillment of meaning, therefore there is always the option that it has a meaning. One could also say that our human existence can be made meaningful “to the very last breath”; as long as we have breath, as long as we are still conscious, we are each responsible for answering life’s questions.

Art from Margaret C. Cook’s 1913 English edition of Leaves of Grass. (Available as a print.)

With this symphonic prelude, Frankl arrives at the essence of what he discovered about the meaning of life in his confrontation with death — a central fact of being at which a great many of humanity’s deepest seers have arrived via one path or another: from Rilke, who so passionately insisted that “death is our friend precisely because it brings us into absolute and passionate presence with all that is here, that is natural, that is love,” to physicist Brian Greene, who so poetically nested our search for meaning into our mortality into the most elemental fact of the universe. Frankl writes:

The fact, and only the fact, that we are mortal, that our lives are finite, that our time is restricted and our possibilities are limited, this fact is what makes it meaningful to do something, to exploit a possibility and make it become a reality, to fulfill it, to use our time and occupy it. Death gives us a compulsion to do so. Therefore, death forms the background against which our act of being becomes a responsibility.

The fact, and only the fact, that we are mortal, that our lives are finite, that our time is restricted and our possibilities are limited, this fact is what makes it meaningful to do something, to exploit a possibility and make it become a reality, to fulfill it, to use our time and occupy it. Death gives us a compulsion to do so. Therefore, death forms the background against which our act of being becomes a responsibility.

[…]

Death is a meaningful part of life, just like human suffering. Both do not rob the existence of human beings of meaning but make it meaningful in the first place. Thus, it is precisely the uniqueness of our existence in the world, the irretrievability of our lifetime, the irrevocability of everything with which we fill it — or leave unfulfilled — that gives our existence significance. But it is not only the uniqueness of an individual life as a whole that gives it importance, it is also the uniqueness of every day, every hour, every moment that represents something that loads our existence with the weight of a terrible and yet so beautiful responsibility! Any hour whose demands we do not fulfill, or fulfill halfheartedly, this hour is forfeited, forfeited “for all eternity.” Conversely, what we achieve by seizing the moment is, once and for all, rescued into reality, into a reality in which it is only apparently “canceled out” by becoming the past. In truth, it has actually been preserved, in the sense of being kept safe. Having been is in this sense perhaps even the safest form of being. The “being,” the reality that we have rescued into the past in this way, can no longer be harmed by transitoriness.

In the remainder of the slender and splendid Yes to Life, Frankl goes on to explore how the imperfections of human nature add to, rather than subtract from, the meaningfulness of our lives and what it means for us to be responsible for our own existence. Complement it with Mary Shelley, writing two centuries ago about a pandemic-savaged world, on what makes life worth living, Walt Whitman contemplating this question after surviving a paralytic stroke, and a vitalizing cosmic antidote to the fear of death from astrophysicist and poet Rebecca Elson, then revisit Frankl on humor as lifeline to sanity and survival.

No comments:

Post a Comment