Nicaragua’s Dreadful Duumvirate

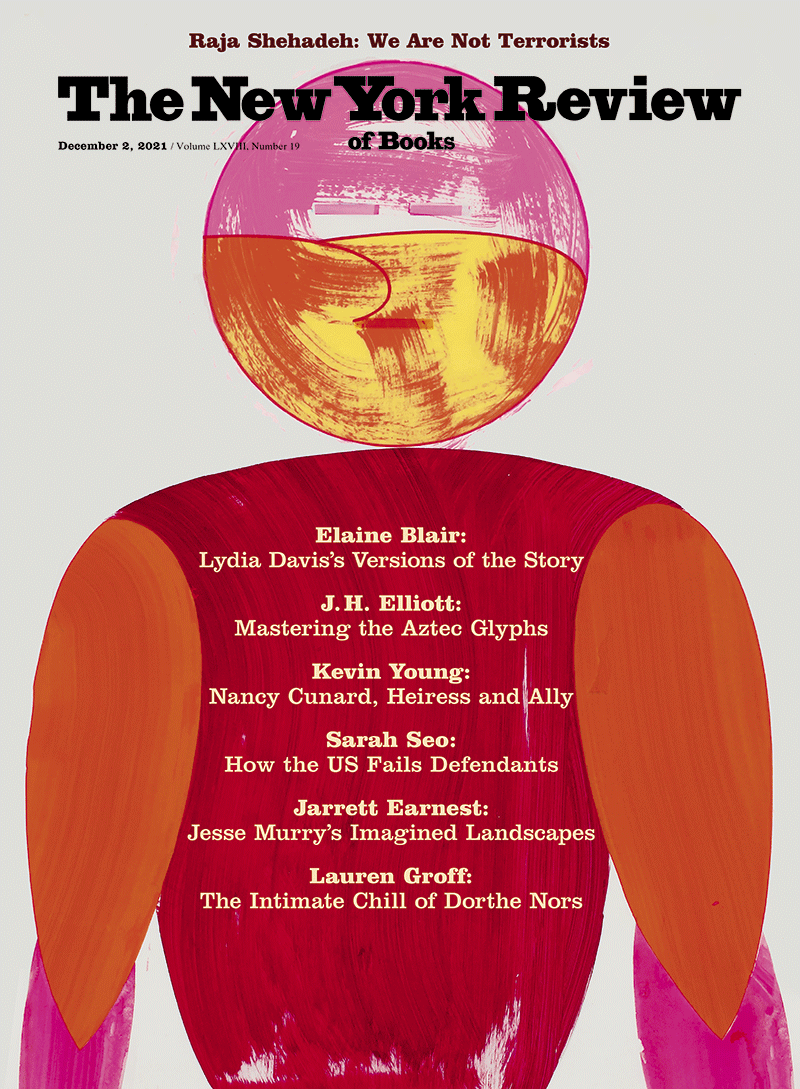

Oswaldo Rivas/Reuters

Nicaraguan vice-president Rosario Murillo and president Daniel Ortega, Managua, July 2015

Sergio Ramírez, the illustrious historian, novelist, and former vice-president of Nicaragua, could well have been among his unfortunate friends and many other members of the opposition arrested by the regime of President Daniel Ortega and his weird wife and vice-president, Rosario Murillo, beginning in June. But in view of the fate of their friends and colleagues, Ramírez and his wife, Tulita, decided to leave Nicaragua. It was a wise move: in September Ramírez learned that he stands accused of money laundering and something called “provocation, proposition, and conspiracy.”

Ramírez is seventy-nine, and it is a cruel fate for someone who loves and has served his country as consistently as he has to know that he may never see it again, or his imprisoned friends, or his beloved writing desk and its surrounding walls of books. On the other hand, all experience is fodder to a writer, and Ramírez’s rich array of novels and historical essays—sixty years of ceaseless production—is a tribute to the tragic and absurd history of his beautiful homeland. Nicaraguans survive their lot with a trickster’s sense of humor, and Ramírez’s latest novel, Tongolele no sabía bailar (“Tongolele Had No Rhythm” might be the best translation of a title as clumsy as its protagonist), is a grim, wildly funny, surrealistic account of the grievous events of the spring of 2018, when student protests broke out in Managua and other cities around the country, and the repression served up by Ortega and Murillo left three hundred dead.

Ramírez tells the story through the character of Detective Dolores Morales, who was severely wounded in the fight to overthrow the dictator Anastasio Somoza back in the 1970s and wears a leg prosthesis as a result. The book’s other characters, however—all portrayed with swift dialogue and the author’s unerring ear for the sweet and extravagant Spanish of Nicaragua, with its sixteenth-century thees and thous and wild similes, and its joyful use of vulgarity whenever the occasion demands—are the most fascinating. They include Tongolele, a top intelligence officer working in the darkest corners of the government; a mild-mannered and heroic country priest; a startling woman who runs all the itinerant salesmen and -women in the country, with a sideline gathering intelligence for Tongolele; and a mystical spiritual adviser to someone referred to only as la compañera. That someone would be Vice-President Murillo, and though she is never seen or even named in the novel, Ramírez avails himself of the opportunity to trample merrily all over her shadow.

The novel’s account of the events of May 2018 is accurate, but it is when Ramírez’s narrative invention runs wildest that his portrayal of Nicaragua under the thumb of the improbable Ortega-Murillo duumvirate is most truthful. Because he was vice-president or the equivalent for the first ten years of the Sandinista regime, Ramírez has intimate knowledge of Ortega and his associates in the underworld of power, as well as of everyday Nica life. Non-Nicaraguans, though, might benefit from a decoder.

Ortega, seventy-six, loves to use the insult vendepatria—fatherland-seller—but he once agreed to sell the rights to a 278-kilometer-long strip of Nicaragua running from the Atlantic to the Pacific to a shadowy Chinese businessman who intended to build a canal parallel to and competitive with the one in Panama. Murillo, seventy, keeps meticulous track of every offense or snub she has ever suffered and communes with spirits who let her know who her hidden enemies are. Police and army battalions being insufficient to hold all the couple’s adversaries at bay, paramilitary groups are now deployed against peaceful demonstrators. Murillo had colorful curlicue metal silhouettes of trees installed all over Managua to channel positive energy from the skies. Strong evidence would indicate that Ortega is a pedophile and a rapist. Together, the doddering couple have created what Monsignor Silvio Báez, the auxiliary bishop of Managua (currently in exile) has called “a situation of…irrationality, violence and evil that surpasses the imagination.”

No comments:

Post a Comment