Highly Snackable

FROG HOSPITAL -- Feb. 17, 2020

Africa

By Fred Owens

I started writing a story about the time I spent a year in Africa and married an African woman and built a small garden. It was so far away from here, in Zimbabwe in 1997. I started writing a story and the first sentence was, "I wish I had never gone to Africa." Then I stopped writing. Who wants to read a story like that? People want to read something more encouraging and not so dark. I thought I could just color it pretty like the movie Out of Africa with Meryl Streep and Robert Redford, I could keep out most of the bad parts, like the time I got robbed and beaten in Jo Burg. I could make the story more appealing that way with drama, adventure and beauty under vast African skies. I could write this story so well and so convincingly that afterward I would not be able to tell what were the true parts and what were the parts I created from my dreams. It would have to be considered fiction, with that formal designation of genre. Or just call it a story, like the stories my wife told. She could walk ten minutes to the local market to buy tomatoes for dinner and come back with a story. And tell me the story one way, then, when her sister came to visit, tell the story another way. She had no concept of truth. I would get mad at her and say stop lying, just say what actually happened. She could not do that. I would get madder -- are there any facts in Africa? None. Not a single fact from Cairo to Capetown. Fact-free Africa. There was nothing I could do about it.

Now, today, this morning, Feb. 18, it is four days after Valentine's Day and two weeks until the Super Tuesday presidential primary on March 3. My plan was to stop the African story and begin some words about the current situation. But I can only pass on a brief conversation I had with my sister Carolyn Therese, older than me by two years. She is a retired teacher from the Los Angeles public schools. Carolyn has lived her adult life in the exciting village of Venice near the beach. She knows many people and frequently talks to them about current affairs. So, besides being a wonderful sister, I consider her to be an excellent source. With that in mind I called her last night and asked her, "Who is going to win the primary on March Third?" She said, "I don't know. I have asked many people how they will vote but nobody has made up their mind yet." That is what she said and that is a fact. We have many facts in our country, unlike Africa, which has many stories and hardly any facts.

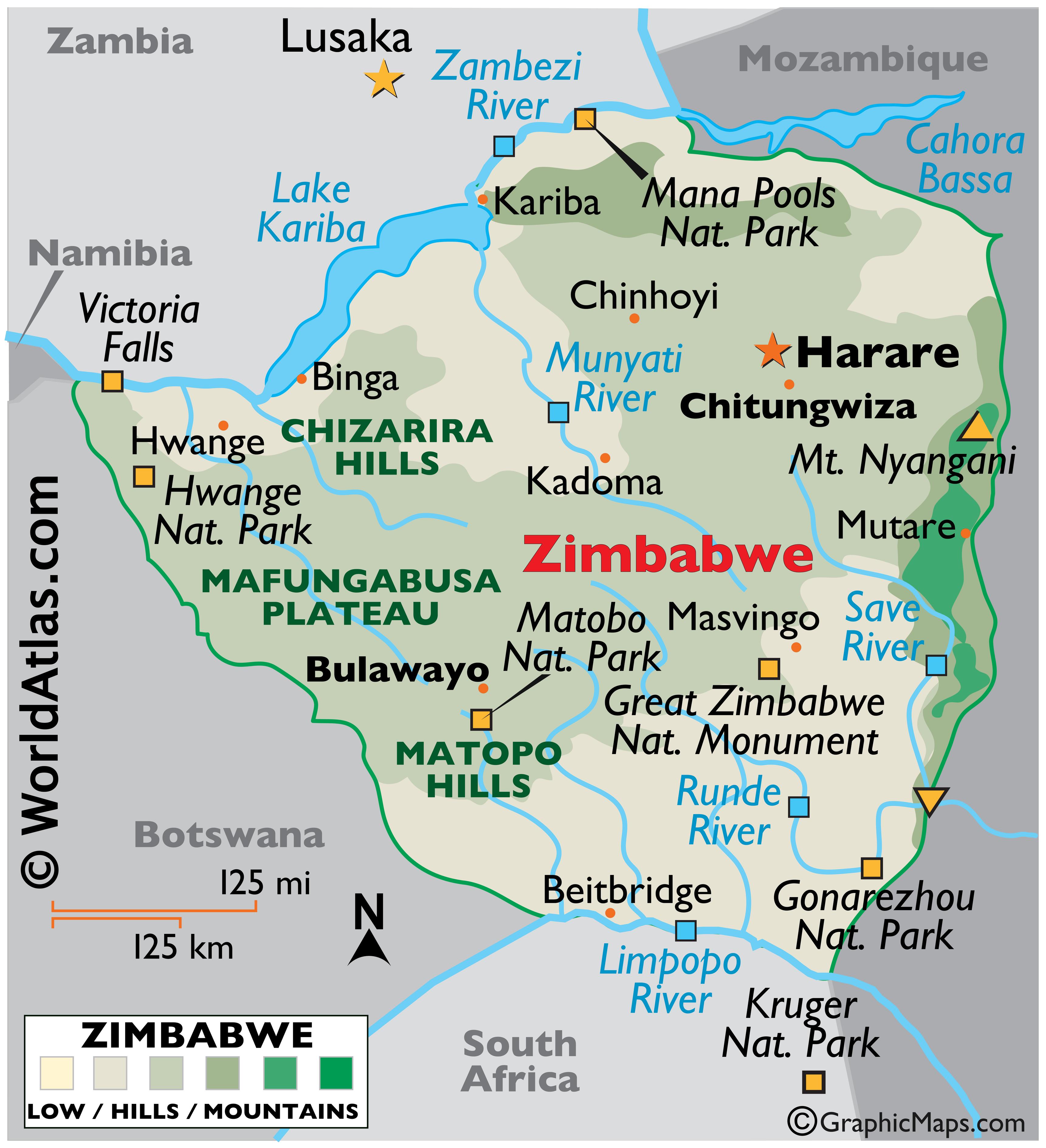

Botswana is a round country, you can see that on the map. Botswana borders South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Namibia. Actually Botswana is a bit angular on the map that I just looked at, but it feels round to me. Also landlocked, which is the term we use to say no beach, no saltwater, no harbor, and no ocean. It is true that all rivers run to the sea, but Botswana has almost no rivers, except for the headwaters of the Limpopo River. I love that name, Limpopo, Limpopo. Rudyard Kipling wrote, "Go to the banks of the great grey-green, greasy Limpopo River, all set about with fever-trees, and find out." I did find out. I saw the Limpopo, saw the water-loving fever trees on the banks. I didn't see the crocodiles, but I'm sure they saw me.

I flew over the Limpopo at a low altitude in a two seater ultra-light aircraft, piloted by a wealthy South African white man who owned a large ranch on the banks of the Limpopo, called Sentinel Farm. We stayed at Sentinel Farm for several days looking at acacia trees. This was on a weekend expedition of the Zimbabwe Tree Society, a group of amateur botanists, mostly local people of British descent who loved trees.

Jonathan Timberlake had very fair freckled skin and red hair. He had written a guide book to the acacia trees of Zimbabwe and their many varieties. Poor Jonathan, as much as he loved Africa, the sun was killing his skin and he must venture outdoors swathed from head to toe in light cotton covering to shield himself from the sun. I heard later that he was forced to return to England because of this. I should make an editorial comment. It goes like this. Some white people get to live in Africa their whole lives. But many white people only get to live there for a certain amount of time -- a year, a decade, a few months. You never know how long. and it doesn't matter how much you want to stay or how much that you feel that Africa is the core of your soul's purest meaning. It's a mystery, but one day you're on a plane back to England, or to the states. And it's final, you can't come back. I'm not sure about that last part. Maybe you can come back to Africa. I will explore that idea later.

But at Sentinel Farm, beside the great grey-green greasy Limpopo river, the members of the Zimbabwe Tree Society wandered about the many thousands of acres of land which the white man owned, although there seemed to be entire villages of local people living there. In any event we weren' t there to discuss colonial history, we were there with magnifying glasses to examine the spores on the underside of the leaves of the acacia trees, and to look at bugs and flying insects and butterflies that might serve as pollinators, and to look at the vast blue African sky.

Besides having a genuine interest in acacia trees, I joined the Zimbabwe Tree Society because we camped on expensive safari property at the local rate. Tourists would have paid hundreds of dollars for a tour of Sentinel Farm.

The Study Manual for this week's Frog Hospital newsletter is a novel titled The Tears of the Giraffe, written by Alexander McCall Smith, about the No. 1 Ladies Detective Agency which is owned and managed by Precious Ramotswe. The book takes place in Gabarone, the capital of Botswana. When I was in Botswana I encountered many people who appeared to be characters in this novel. I will marshal more facts about Botswana, but to learn about these people, read this fictional book, or any of the many other novels written about Precious Ramotswe, proprietor of the No. 1 Ladies Detective Agency.

And be sure to vote on March 3,

And, with regard to the corona virus, be sure to wash your hands frequently with hot water and soap.

Until next time, your friend always,

Fred

--

Fred Owens

1,164 Words 1,164

FROG HOSPITAL -- Feb. 22, 2020

I Wish I Had Never Gone to Africa

By Fred Owens

"I wish I had never gone to Africa." Already I'm getting tired of that opening line. Readers are encouraged to supply a replacement. Maybe from the old Bob Dylan song, "I'd like to spend some time in Mozambique."

Jerry Thebe lived in a shed in our backyard in Bulawayo (a solid brick shed with shower, toilet and electricity, quite a decent shed). His parents owned the house we rented. His family came from Botswana. And what language do they speak in Botswana? Setswana. They speak Setswana. That's their language. Ba- is a prefix that means people. Mo- is a prefix that means person. So Jerry is a Motswana who comes from Botswana. and speaks Setswana. That is our first lesson in African languages.

Jerry also speaks Shona, Ndebele, Xhosa and English. Maybe some Kalanga and Tonga. Most Africans know at least three languages and have an impressive vocabulary, at least as large as mine. When I first got to Africa I was riding a bus from Pretoria, across the Limpopo River into Zimbabwe on my way to Bulawayo, which is a day long trip, counting an hour or so at customs. The three young men sitting in front of me were speaking and laughing to each other with great enthusiasm. The beer they were drinking seemed to spur the verbal antics. But they weren't just speaking and telling jokes. They were playing with the language itself. They didn't just speak three languages. They spoke three languages at the same time, because that's more fun. And they laughed and drank more beer. It was ten a.m. We stopped for lunch at noon. They had huge plates of sadza and nyama, followed by more beers. They piled back on the bus and fell asleep. I enjoyed the quiet as the bus rolled along and contemplated my own inadequate grasp of English.

I was forgetting about Jerry Thebe. He lived in our backyard for more than a year and studied software and computer usage. Later he moved to Gaborone, the capital of Botswana, where he worked in software. I last heard from him by email about ten years ago. I am trying to locate him now. He would be forty-something and likely has his own family. I would bet he's still in Gaborone, which is not such a large city. It would be fun to go looking for him. It is fun to find people --- when you're intentions are innocent, as mine are.

I also looked up Jonathan Timberlake, the botanist who published the authoritative guide to the acacias of Zimbabwe. As I said last week, he needed a sabbatical in the cloudy country of his native England. His fair skin was causing too much cancer. But he continued his work and edited the Flora Zambesiaca, which features a complete list and description of all the plants species in Zambia, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, and Malawi. The project was started in 1950 and it has cataloged 24,000 species as of 2012, in multiple volumes, sponsored by the Herbarium at the Royal Gardens in Kew.

Botany is such happy work. I imagine Jonathan Timberlake is fully absorbed in this project. And he too has quite an impressive vocabulary. I am trying to locate his email address. We did not get to know each other well when we botanized together in 1997, but he would welcome inquiries from a fellow enthusiast as I am.

She. She is the title of an Africa fantasy novel by Rider Haggard. He is the third person I would like to contact, besides Jerry Thebe and Jonathan Timberlake, except Haggard is dead, so this will have to be done telepathically. What will I say to him? Mr Haggard, did you really just make this up? Rider Haggard also wrote King Solomon's Mine, published in 1885, which I absorbed. Here is what Wikipedia says, "Rider Haggard has been widely criticized for perpetuating negative stereotypes about non-Europeans." True, but they didn't tell me that. I covered my ears. The fantasy was too rich. Knowing full well that there was absolutely no truth to this claim, I became quite certain that King Solomon's Mine actually existed and could be located in the Matopos Hills outside of Bulawayo, guarded by leopards with gleaming eyes. Ingwe means leopard in the Ndbele language. We sometimes drove out from Bulawayo and spent the afternoon by the pool at the Ingwe Lodge in the Matopos Hills. We drank Bollinger's beer and my wife went in the pool and began to learn to swim. There are leopards in the hills of Matopos, and caves that hosted traditional ceremonies. And the buried treasures? You know they had to be around there somewhere, rubies and diamonds. I could sense it. Matopos isn't just magical it's extra-terrestrial.

I decided to leave out the part about the rumored, but never proven, affair between director John Huston and artist Frida Kahlo. This affair culiminated in Kahlo's arrival at the movie set in 1951. Huston was filming live on location on a tributary of the Congo River for the movie African Queen. That movie was adapted from CS Forester's novel of the same name published in 1935. The movie starred Humphrey Bogart as Charlie Allnut, the drunken captain of the African Queen, and his companion Rose Sayer, the missionary sister, played by Katherine Hepburn. Both the book and the movie were a huge success. Accurate or not, these tales form the basis of what we know about Africa. But the part that fascinated me the most was Kahlo's secret journey to the movie set, for her clandestine liaison with Director Huston. He lied to her and told her she would have a major role to play in the film. She knew he was lying. They fought. She came down with a tropical fever and almost died. Huston continued drinking Gordon's Gin with Bogart. Hepburn had brought her tennis racket with her to Africa but found it quite useless and it began to warp in the tropical heat. None of this can be substantiated however, so I must leave it out of the story. Some lies are too fantastic.

The next issue will introduce the Mataka family from Bulawayo and the woman I married. I'm trying to give her some fan fare before she enters this humble story. I will undoubtedly seem dismissive, patronizing, disillusioned, uninformed and egotistical. I will try, but almost surely fail, to step out of the way and let the story tell itself.

In the meantime, God Speed,

Fred

2,268 words

Zambesi River

FROG HOSPITAL -- Feb. 27, 2020

I Had a Farm in Africa

By Fred Owens

"I had a farm in Africa" is the famous opening line of Out of Africa, Karen Blixen's lyrical meditation of her life on a coffee plantation in Kenya in the old colonial days. "I had a farm in Africa, at the foot of the Ngong Hills." I don't need to read the book again or see the movie again. I can just say that opening line, close my eyes and dream it. I didn't have a farm in Africa, but I did have a garden with tomatoes and strawberries and African herbs. The garden was at our rented home at 21 Shottery Crescent in Bulawayo. We lived there for most of a year and spent many hot afternoons sitting in the shade of the pepper tree. So how did I get there.

I will start at the beginning. My mother died in 1996 at her home in Wilmette, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago. That was where I grew up. I came home for the last time for her funeral and for the months-long project of clearing out the house and settling the estate. I was 50 years old, a single parent. I had just sent my younger child off to college, and I was free. I had moved out of my apartment after Eva left for school. I sold and gave away most of my furniture and put the rest in storage in the attic of Pam Fleetman's garage. And my mother died --- I know I already said that once, but it was an enormous change, not so much that I was sad, because I was not sad, but I was totally dumbfounded and dazed.

By the new year of 1997, I had emptied the old house and it was ready for sale. Mom left us some money, it was more than I expected, money I didn't earn and didn't especially deserve, but I guess it was a gift, a bonus that I could use to go someplace, almost any place, and not to travel there but to live there. I chose Africa, for the reason that was obvious to me because it was January in Chicago and it was freezing out there. I would go to Africa to be warm and to live there for a while, have a life with a house and friends and some work. Get to know the people and the climate, find a coffee shop or tavern or bookstore where I might pass the time. Study the plant life, especially the baobob tree. And learn the language and hear the music. So far away to Africa, over 8,000 miles from Chicago, and in the southern hemisphere to see stars I had never seen before.

I chose to live in Zimbabwe because Doris Lessing grew up there. I read her autobiography Under My Skin describing her life as a free-spirited young girl on a farm in the bush in old Rhodesia. As an adult writer with radical views she came into severe disfavor with the white Rhodesian government and was sent into exile, back to England.

Lessing returned in triumph after the 1980 victory of the revolution which brought home rule to the people of a country now called Zimbabwe. The new government gave her a farm. She was grateful for that but could not keep her words to herself. She wrote about the violence and corruption of the liberation government, finding it to be scarcely superior to the old white government. So she was sent into exile a second time, possibly the only writer to accomplish that feat.

I bought a ticket and got a visa. I booked a cab to O'Hare Airport. When the cab came early the next morning, I soldiered out of the home where we had lived for fifty years, resolutely determined not to turn my head and take one last look. For me, my mother and that house were one and the same thing, but it was good bye. I should have realized that I had just become homeless.

Capetown is like a southern California beach town. Africa Lite. Lots of white people living in nice homes with ocean views. I took the third floor garret room at the lodge in Kalk Bay managed by Mia and Fatima Lahrer, a charming Indian couple. We had many vigorous conversations over dinner. I could see the warm waters of the Indian Ocean from my garret window. I might go body surfing at the nearby beach and then stop at the Cafe Matisse for a glass of wine and a flirtation with Rose the beautiful Coloured waitress. I might have drinks in the evening with Michael Pam, the old poet of Kalk Bay. I might go hike on Table Mountain with the local botany club and see the flowers that grow there and nowhere else -- what they call endemic. I had friends and I had a life in Kalk Bay. It felt more like Europe than Africa.

Then I called Eva my daughter and reached her at her dorm room in Oberlin College in Ohio. I told her that I had found my place. and she said, without a pause, Dad, that's not Africa, you said you were going to Africa. You can't just lie on the beach. C'mon, Dad. .... She could be so commanding. I must follow my mandate and launch a serious expedition into the heart of it. Take the plunge. Go there. Be there. This was not a vacation, but a quest.

That evening at dinner with Mia and Fatima I told them I must continue my journey to Zimbabwe. And Fatima said, You must go to Nyanga. I said why Nyanga, what is there, what does it mean. And she said, You must go to there, you must go to Nyanga.

The End, but stay tuned for the next chapter.... Nyanga means Moon in the Shona language. Let us go there together.

And don't worry about the virus too much. Wash your hands more often, cough into your sleeve, stay home if you feel flu-ish ... but the mask hardly seems necessary unless you work in health care.

Hope it rains here in Santa Barbara and soon,

Hope you all get the best weather you can dream,

Closing in gratitude,

Fred

3,332 words

FROG HOSPITAL -- March 2, 2020

Why Are You Walking Alone?

By Fred Owens

Going to Nyanga, as I said, but it takes time. I am writing this story as an email installment serial -- writing in chunks of a thousand words, getting feedback from a panel of dedicated readers who have ideas of their own as to where this story is going, but I know where this story is going, I can see it in my mind, everything but the ending......Is there a hurry? I already skipped lightly through Capetown and forgot to mention that I waved at Nelson Mandela as he rode through the street in his limousine on his way to the opening of the South African Parliament. Nelson Mandela himself. But I skipped that part of the story because I got a message from Fatima Lahrer to go to Nyanga, and I got a boost from my daughter Eva who called me from Ohio saying it was time to move on from Capetown. I didn't fly 8,000 miles from Chicago to Capetown just to lie on the beach --- but the waters of the Indian Ocean were so warm!

It takes 800 miles from Capetown to Johannesburg. You can fly. And the express train serves very well.... but I took the bus because I wanted to look out the window and see the veld. I took the bus for 200 miles going due north, to Calvinia, a nothing town, where I planned to do nothing. Nobody goes to Calvinia, why would they? With ten thousand people surrounded by semi-desert grazing land full of cows. Not giraffes and zebras and ostriches .... just cows.

Calvinia was named after John Calvin, the gloomy Swiss religious reformer who preached the predestination of all souls, that we were doomed to hell or to be anointed in heaven, our fate was decided from birth and we had no choice. Calvinia was founded by Afrikaaners who practiced this gloomy religion amidst their cows, in the veld, in country that looked a lot like West Texas. Except this was really Africa. The Afrikaaners have their own language. They don't like the English. They didn't like me, except for the manager of the hotel who made a completely phony effort to be friendly with me, "Hey, buddy, How's it?"

I went to my room, stretched out on the bed, and started reading the last 100 pages of Doris Lessing's autobiography, Under My Skin about her childhood in Zimbabwe. Then I went out for a walk, through the town, but there is nothing to see in that town and I liked that because I just wanted to walk. Then I walked out of the town into the fields, and why was I walking alone? This walking gave me a chance to think, or really, to unthink, to be in Africa, just breathing and walking and feeling the earth.

I saw the cattle grazing. This is dry country. The first people were the San, the hunter-gatherers. They lived for many thousands of years in all of southern Africa --- had the place to themselves, as it were, occupying some of the dry country but also the more abundant country that got rain. Then the KhoiKhoi came drifting down from central Africa, driving their cattle, because they were pastoralists, and not hunter-gatherers. They pushed the San people aside and took over the greener fields for the cows. Many thousands of years ago this happened. The San people moved deeper into the Kalahari Desert where the cattle could not graze.

In turn, the KhoiKhois were pushed aside by the Bantu people migrating from Cameroon, bringing cows and crops, enslaving the San people and the KhoiKhoi. The Bantu farmed and grew millet and made beer from the millet. Then came the Afrikaaners who whipped and enslaved the Bantus, and drove off the San people because they were unfit for labor. And finally the English came with their Queen Victoria and ruled over all, that is, until Nelson Mandela and the African National Congress took back the country for themselves and now the Bantu people dwell in their own land, and might evict the Afrikaaners and the English. And what do the San people say about all this, when it all used to be theirs? What do I say about all this? I can only say This is Africa and I am here now.

This is what I thought about when I walked alone in the fields, the veld, outside of Calvinia, where the scenery is far from spectacular although they told me people come in the springtime to see the wild flowers. But you see the cattle, spread out to the horizon and the African people love their cows more than anything. They never de-horn the cows but admire the long curves of the horns. Cattle is wealth. Cattle is the bride-price or lobolo. Nelson Mandela finally divorced his wife Winnie because she was so difficult to live with and he yearned for a kinder woman to see him through his elder years. That wife-to-be was Grace Machel, the widow of Samora Machel. who had been the President of neighboring Mozambique until he died in a mysterious plane crash in 1986. But in 1998, to overcome his solitude, Mandela married Grace Machel and his clan sent a herd of cattle to her clan. That is the lobolo, the bride-price. The amount is negotiated. It can be a very elaborate deal. It can be very enjoyable to dicker and all the relatives have an opinion about the worth of this cow or that cow. And the modern bride objects to being part of a bargain with cows. Am I being sold, she cries out. I went to college, she says, I have a degree. And her mother says of course, and because you are educated and earn a living you are worth that much more. Your husband-to-be will have to pay more. This sounds ugly when you think in terms of money, but cows are beautiful in their own right and never ugly to the people of Africa.

But I was walking in the field, not thinking about all that but wondering, what the hell am I doing in Africa? And why am I going to Nyanga because I refused to look it up in the guide book, because it was one of those missions where you don't ask questions or look for details, you just go to Nyanga because Fatima Lahrer said to do that and my daughter Eva said so too.

Walking alone in the veld far from town, not being from there, not being a tourist on the tourist trail, not being a volunteer working as part of a non-profit development project, not having a recognized project to extol. I was a long way from town now, picking up rocks, not to keep, just to examine. I needed time to adjust.

I got back on the bus and rode to Johannesburg. We won't stop long in Johannesburg, just change buses for Zimbabwe. Jo-Burg, violent, dangerous, gold mines, fast cars, weapons -- migrants from poorer countries come to Jo-burg for work.

The End.....

Too much news these days, the virus, the election, and the stock market ..... Let us all take a deep breath and embrace -- hold it -- embracing is getting kind of doubtful -- maybe air kisses and friendly waves.......

Take care,

Fred

4,571 words in four sections

FROG HOSPITAL -- March 6, 2020

The Rain Queen

By Fred Owens

I checked out of the hotel in Calvinia. I walked over to the gas station at the edge of town. The bus was coming at midnight. I got there early because I like to get places early. I looked at the stars. It was very quiet on the outside of town. The bus was an express to Johannesburg and we got there the next day. I had a four-hour layover to get the bus to Zimbabwe. I checked my bags and took a walk. I think I walked out the wrong door because the neighborhood looked a little seamy. There were a few vendors with their wares displayed on blankets. I was going to visit the Johanneburg Stock Exchange where I might view traders in frantic motion buying and selling shares in the gold mines which tunneled under the busy sidewalks of this great city. Gold. Five thousand feet down. Sweating mine workers. Dangerous work in the mines. Up above the gold was traded in the Stock Exchange. I could view the action from a balcony reserved for visitors.

So I headed in that direction, down this seamy street with vendors showing their wares on blankets. An urchin came up to me and asked me where I was going. He didn't ask for money. I told him where I was going. He said a quicker way was down that street, pointing somewhere. Why was I walking alone? I went down this side street, too quiet. Two men jumped me. One in front with a dead look on his face. The other in back grabbing my arms. They threw me to the ground and grabbed at my back pocket, ripping my pants, gashing my blood, and grabbing $50 worth of currency in Rands from my pocket. Then they ran off. Ten seconds and done. These guys were pros. I'm glad they ripped my pants and gashed my blood, because then they didn't need to kick me. I'm glad they ripped my back pocket and took the cash, because I had my wallet and passport tucked inside my pants in a money belt and they didn't get that.

This could have happened in an American city, except in truth, Johannesburg has a much higher crime rate. Crooks are armed. Citizens are armed. Egoli is the Zulu name for this godless city. Gold. Money. Crime. I limped back to the bus station, put on fresh pants, threw away the ripped and bloody pants. Found a cup of coffee. Replenished my nerves. And just to feel like a winner. I asked around to find the right door out of the bus station, the one where all the tourists go, to the nicer part of town and heavily policed. I walked out there and I said this is the well-beaten track. This is a good view. It's safe. But when you wander off the track and you're walking alone, you better pay attention. Why didn't the urchin ask me for money? I should have wondered.

The Rain Queen died in 2005 after only a few years on the throne. It is suspected she died of AIDS. She was not supposed to have a boy friend. The Rain Queen must maintain a semblance of virtue and mating only with men of noble birth. But of course she had a boyfriend, a back door man. Don't Ask, and Don't Tell. But she didn't do that. The boy friend appeared at her side in public and the matrons of her court were shocked and angered. Then she died an early death. Here is something I learned about African people. Nobody dies of AIDS. I knew many young people who died, much younger than me. What did they die of, and they family always said the same thing -- Otherwise has had cancer. Really? Cancer? This is Africa. I did not come to challenger or change local custom. If you say it's cancer, then it's cancer. After that I never asked how they died. It was just sad. So the Rain Queen died and she has not been replaced.

Too many people died when we lived in our rented house on 21 Shottery Crescent in Bulawayo. Christopher died. Francis died. Maphuto had velvet black skin and he died. Aunt Janet was my favorite. She was much younger then me and she died. We took her in a casket out to the cemetery and there were six other funerals going on that day, digging graves. But I stopped asking how they died.

I brought a small sketch book with me with colored pencils. I did not have a camera. They steal cameras, and the weather can ruin them and you need to buy film, and you might offend local culture by pointing your camera at someone or something. But nobody minds a sketch pad. They come up to you and say "I see you are arting. Is it fine?" And I would reply, "Yes, I am arting that bird, which is sitting in that tree." And the man would lower his head and look closer at the drawing, "Yes, you have made a good drawing." "Can I give it to you?" I might say, if I truly wanted to share. But when you bring out a camera, people get stiff and self-conscious. Later I bought a camera and brought it to weddings because African people expect that and they are wearing their best clothes at a wedding.

We crossed the Limpopo River into Zimbabwe. The people crowded around the customs station selling things. They were black. It dawned on me like Forrest Gump sitting on a park bench. Black people live here. Not mixed blood Coloured people like Hugh Masekela, the jazz trumpeter from Capetown, but all-black people. In America you can go to a part of town and that's where the black people live. So you are used to that. Okay, now I'm in the black part of town. But in Africa it's everything. It is all-black. There is no place or thing or tree or person that is not black. It's not really scary but it's awesome. People on the bus ignored me. I don't think they noticed or cared. There's this white man on the bus. In Zimbabwe they call a white man a kiwa. Kiwa is the Shona word for fig. The inside of a fig is pale pink, so a white man is a kiwa. I heard people say that, in kindness. But it's all-black. Is there any part of Africa that is not all-black? Yes, Capetown, but we're gone from there.

So I just read my book and looked out the window as the bus rolled north to Harare. I had no need to apologize. I was going to stay in Harare for a few days and then head to the Eastern Highlands to find Nyanga.

Then I will write about my wife. That could be the best part of the story, but I am building up to that. I am surprised about how much I remember.

I heard from Judy in LaConner and from Mary in the Hollywood Hills asking the same thing. When are we going to hear about your wife? Soon.

The End

Current Events. Current events -- the virus, the election, and the stock market crash -- can be overwhelming. It is important for all of us to stay calm and stay grounded. I offer this African story as a kind of escape, a journey to another reality. Please send me your reaction to this story. Where do you want it to go? What did I forget?

take care,

Fred

5,858 words

FROG HOSPITAL -- March 9, 2020

Precious

By Fred Owens

"Precious ....... My name is Precious," she said. She sat across the table and looked at me. Precious was wearing large gold hoop earrings and a white knit sleeveless shirt over well-fitted black jeans. Her hair was short and natural. She had bright red lips, but I think that was just me imagining. She twizzled her gin and tonic looking down, then looking up at me with her fabulous big smile.

"Your name is Precious," I said. What was I supposed to say? Quickly rejecting thoughts of saying I never met anyone named Precious before. Or another big thought, Can I touch your hair? No, creepy. So I started talking with Nellie, her companion. Nellie spoke better English anyway. Nellie was there, at the Palace Hotel in Bulawayo in what was probably a professional capacity. I wasn't interested in Nellie. She was kind of stout and rough and too smart. I was a little wary of her.

But Precious was fresh and bursting with life. She may have been playing a game, but there was so much more going on. I wanted to talk with her, so I asked her her name. Precious did not speak English as well and of course I knew no Ndbele, except Nkomo which means cow and a few other words.

I had been enjoying a solitary beer on the large shaded patio of the hotel on a quiet evening. Joseph the waiter had been serving me. I already felt Joseph and I had been best friends for a long time. Good waiters are like that. The Palace Hotel was a colonial remnant in the heart of Bulawayo. A black man could not get a drink there until 1980 when Rhodesia became Zimbabwe. Nothing had change since then. They still had the large carvings in the lobby, of pseudo-African chieftains, the kind of carvings that old Rhodesians could ignore because they were wooden dummies. Except the Rhodesians had been scattered when Robert Mugabe and his Shona soldiers took over.

Joseph was mid-50, had probably worked in this patio serving drinks for his adult life, seeing people come and go. "Joseph, could you buy those ladies a drink? " I said. I pointed to the only two ladies in the patio. I never did things like that. My whole life I was much too shy to try anything like "buy these ladies a drink." But I did that night. And Joseph went over and whispered into Nellie's ear. The two ladies looked at me smiling and came over to my table. So began the next seven years of my life. I was no longer walking alone.

Joseph hovered tactfully, black pants, baggy white shirt, loose tie, thinning grey hair, happy but understated smile because he knew something was happening. "We have some nice roast chicken if ...." That sounds good, I said, would you ladies like to eat? Precious said yes. She had a husky voice with warm tones, quiet. She had an athletic build with strong shoulders.

"Where do you live?" I asked her. She said, I live in Luveve at the house of my grandfather Mr. Mataka. Luveve means butterfly.... "So there are lots of butterflies in Luveve?" I said. No, she said, that is not how we do it. I will tell you. There was a man who owned a small store and he could never sit still. He would always jump up from his chair and move his arms about up and down and be excited, so we called him Luveve --- Mr. Butterfly. So that was the name of the store and that is where the bus stopped, at Luveve, so now that is the name of the town. "Is Mr. Butterfly still there?" I said. No, he died.

Jospeh brought out big plates of roasted chicken, with piles of sadza, the stiff and white cornmeal mush which is the staple food of all Zimbabwe, and a side dish of boiled collard greens. Precious and Nellie ate with gusto. The patio was quiet. Few customers, soft music, muted kitchen noises, no traffic noise from the street. I was beginning to forget everything or where we were or what we were doing. For no reason I looked at Precious and said, "You're a pretty lady, you're sweet like a bowl of raspberry sherbert. " She smiled. What is raspberry sherbert, she asked. "Ice cream. You are sweet like ice cream."

I was embarrassed. I had been in Africa for one month and had absolutely not looked at any women in that way, had not even considered, you know. just had not considered. There was a huge barrier of race and culture. That barrier didn't bother me. I would not challenge it. Except the barrier was down that evening.

We left the patio and walked over to the lobby, the three of us, kind of awkward, but I was thinking and then I said to Nellie, Did you need cab fare? I pulled out a large note of Zimbabwe dollars. She took it and left. Precious and I looked at each other and then looked at the stairs going up to the room. We climbed the stairs together. I could not believe this. I was going to love the African Queen and her name is Precious.

The next morning we went out for breakfast. I can't remember what time it was when we got up. I didn't have a watch or a travel alarm. The bathroom was down the hall, like an old-fashioned hotel, The bathtub was huge, could easily drown a six- footer. The commode and toilet could have been cleaner. I didn't care. I had a companion. She had no interest in improving her English and did not care to teach me Ndebele. We would do fine without too many words. We talked all the time and said the same things over and over. We ate breakfast at a sunny cafe. I don't remember what we ate. She said, Fred, you know I need new shoes. I was not a fool. I knew what to do. When a woman says she needs new shoes, that means she needs new shoes. I said I will buy them for you. And jeans, she said. I need new jeans, Love in Africa can be so transactional. This was too easy. We were taking wonderful advantage of each other.

We got her the jeans. Then, standing outside the little store, she looked at me and said, "You know that I love you, but you are dirty. You need to clean up. You know that white people smell bad to me. You must come with me to my place and freshen up. And we will do something about those clothes." So I got my things from the hotel and we took a cab to her place on Airport Road.

What Happened to Nyanga? Well, I went to Nyanga and other beautiful places, but I decided to skip ahead this week and introduce Precious because she is the main character in this story.

The News. The news is not good. This African story is offered to you as a kind of relief. For the short while that you read it you can imagine yourself in Africa where life can be very wonderful. Sometimes.

Be well, stay healthy, be kind to your friends and neighbors, and fear not,

Fred

7,101 words

FROG HOSPITAL -- March 14, 2020

Ernest the Garden Boy

By Fred Owens

I remember Ernest the Garden Boy when I met him that March in 1997, standing in the corn field on Airport Road. It just occurred to me last night as I was trying to get to sleep that Ernest might still be there. In that garden on Airport Road, 23 years later, hoeing the corn, just like he always did. They would call him sekuru now if he was still there. Sekuru is a Shona word meaning elder.

Do you remember last week when we left off? Precious and I were heading to her room on Airport Road, to get me cleaned up. I had been traveling around Zimbabwe for several weeks, seeing the safari country at Hwange Park, seeing giraffes and zebras and ostriches, elephants, impalas, such a variety of wild game. I saw two giraffes making love. Their necks and legs are very long and it takes them hours just to get in position. The female will kick him off and kick him off until he becomes tender and patient. The male comes in raging like a bull, but she plants her feet and fights him off. It's not easy for two giraffes to couple, but it's worth the effort.

I saw Victoria Falls, the thunder of water falling 300 feet into a narrow gorge. And the Livingstone Baobab Tree which is reputed to be the largest in Africa, near to the water fall. And the hippos, so big and menacing. I traveled alone and got a little rough, so when I got to Bulawayo it was Precious who wanted my presentation to be civilized. People in Zimbabwe are especially clean I learned. For being poor they spend their money on floor wax, shoe polish and laundry soap. Clothes are washed by hand in a bucket or bath tub, not in hot water. Most people have only a cold water tap. Clothes are scrubbed within an inch of their lives and then rinsed and then hung out to dry on a line. Bulawayo has a very dry climate. In Bulawayo most summer days are 95 degrees. Clothes on a clothes line seem to dry before you even turn around. You might have an enduring image of Zimbabwe of a bull elephant with mighty curved tusks, or the lion roaring, or the ostrich prancing. You might have that image and you would be right to have it. But my enduring image of Zimbabwe is clothes drying on a line in front of Precious's small room on Airport Road. Crisp and clean.

Then she ironed everything. Because she was good at it. Most Zimbabweans are. The iron is heavy, five pounds, and has no electricity. You put it on the hot plate and get it heated. Then you iron for ten minutes until it gets cooled off. Repeat. Ironing on a towel on the floor. She ironed everything even T-shirts and boxer trunks and she did it with graceful movements like the tea ceremony. I sat on a metal chair by the door and watched. It took hours. Then I put on my new washed and ironed clothes and it felt like the silk robes of a king. I was not a poor, dirty traveler, but a man of substance and strength, which she gave to me. That's ironing in Zimbabwe. I did see African housekeeping at it best. Floors waxed and polished. Yard swept clean.

Yard sweeping is interesting because nobody has a lawn or any grass, just the hard, red clay and it is swept every few days with a twig broom. Precious would do it. I said, after we had lived together a few months that we could hire another woman to do the laundry and sweep the yard, which is what people do who can afford it. Precious said, "No, I don't want some woman coming to my house and poking into things, I will do it myself." But that was later. And the food. She cooked. On the same hot plate.Those first days together at Airport Road were very good for both of us and I will stop talking about this because it is too personal.

Ernest was out in the yard during all this. He had his own shed in the back for living. Then he would hoe the corn. I never saw a human being move so slowly as Ernest did. This really impressed me. Garden boys don't make a lot of money so there is not much point in getting it all done. Mostly he just stood there like a scarecrow with a vacant stare under his heavy brow. He wore dark blue overalls and black knee-high rubber boots. This is why I think he is still there, because why would he want to leave and where would he go?

A note on terminology. In Rhodesia and in South Africa under apartheid, it was the custom for a white man to refer to a black man as a boy. And it was the custom for the black man to call the white man boss. When the revolution took over this custom was banished. It became illegal to call a black man a boy, and I never heard any body say that. With one exception. For some reason it was still common to refer to the fellow working in the yard as a garden boy. I don't know why this was so.

A note on growing corn. Everyone in Zimbabwe plants corn when the rainy season begins in November. Everyone has the hope that the rain will come and the corn will be abundant. Ernest had surely worked hard in November cultivating that small field and planting the corn. Then he stood there and watched it grow. And stood there for hours and days. I wasn't sure -- he might have been dumb as a brick. Or maybe he had no reason to disturb the silence. The house on Airport Road was a quiet place on the edge of town. The lady of the house, who rented the room in back to Precious -- she was often gone. She was a church lady and very polite. Sometimes, even most of the day, she was gone and Precious was gone, but Ernest stood there and -- I wouldn't say he watched, I would say he was present. Being there -- that was Ernest.

African Night Descending. Ernest went back to his shed to cook his small dinner. The lady of the house was inside watching the TV with her daughter. We sat in those metal chairs in the patio drinking Bollinger's Beer. The sky was getting dark. The African night was descending.

"The sky is so big in Africa," I said.

"Yes, there are too many stars," Precious said.

"We are together now, in this evening light, but we are so different."

"We are not different. We are the same," she said

"But I don't know you."

"You know me. We are the same," she said.

I stretched my legs out under the table and watched the tiny bubbles in the beer glass on the table.

"Can I meet your family?"

"You will meet them. Aunt Janet and Aunt Winnie will come here tomorrow," she said.

The End

Next Time. Aunt Janet and Aunt Winnie came to meet me. We rented a car and took them for a ride. We bought them plenty of beer and fried chicken. They seemed to like me.

Here in Santa Barbara. We've had good rain. I have a three-month supply of prescription medicine. We have a two-pound sack of shelled walnuts, plus many other goodies in the pantry, extra coffee, some beer and wine. We are old-time campers and we will do just fine.

See ya,

Fred

8,406 words

FROG HOSPITAL -- March 17, 2020

Love and Marriage

By Fred Owens

(we are continuing the African story as a public service. This story gives you something to think about besides the virus)

Happy Saint Patrick's Day. First a note about drinking beer. The shebeen is an Irish-Gaelic word denoting an illegal private drinking establishment, often found in Ireland, but just as often found in Zimbabwe and South Africa. So, as I was to learn about Precious's family, her Aunt Margie ran a shebeen in her modest home in Luveve, selling beers from her cooler to local gentlemen who sat in couches in her living room in the evening. I was never there in the evening. That neighborhood was much safer than any place in Johannesburg, but still, being the lone white man in those parts, and fairly ignorant to boot, I always departed before sundown.

As we finished up the last chapter of this story, I told Precious I wanted to meet her family. This was out of curiosity, but also my declaration of a more serious intention. She was already ahead of me in seeing a joint future for the two of us. After all, we had been living together for almost a week. . She said, "Aunt Janet and Aunt Winnie are coming tomorrow. You can meet them."

That was fine with me, but later I wondered about how things got done among African people who don't have phones. How did Precious get a message to her two aunties, that she had a live white gentleman on her hands and he needed to be looked over? She had no phone. The aunties lived in Lobengula and had no phone, and not near to Luveve where lived Aunt Margie, and not near to Entumbane where lived Mister T, which is what everybody called her father. How did any of these relatives know about me? None of them had phones.

Like so many other questions I had about African culture, I got no answer, no explanation of how things worked.. I just said Hey, that's fine. I was going to show the aunties a good time, that part I understood. The aunties liked cold beer, I didn't have to ask about that. They probably liked generous portions of fried chicken. And to impress them I would rent a nice car for the day. We could drive out to Matopos National Park, not one hour out of town. Matopos has the fabulous rock formations and it is a tourist wonder.

The aunties came the next day. Winnie was stout, Janet was small and thin. Winnie had her head shaved, being in mourning for a lost husband. Janet was a spark plug, a live wire. She had the most dazzling smile I have ever seen. Winnie played the sidekick. Janet was the African diva, she had her hair woven in intricate braids. They were both about forty, not too much older than Precious. They wore modest dresses as most women in Zimbabwe did. Precious some times wore jeans to indicate her independent status, but she also wore dresses.

Janet had a husband somewhere. She owned a bottle store -- a general store, but called a bottle store for the beer sold there. The store was in Blantyre in Malawi. Blantyre in Scotland was the birth place and home of the great missionary David Livingstone who gave his life for love of African people. Janet's store had a grinding mill for local farmers to bring their shelled hard corn to grind into cornmeal. Precious told me all that. This was the Malawi branch of the Mataka family. Mataka was Precious's last name. One of her last names. She had several identities. My trick was to never try to figure it out or to ask questions. I saw what I saw and I heard what I heard. And I never asked the really dumb questions -- the dumbest one of all questions was the famous bus question. Go to Africa and try this when you see people standing by the side of the road waiting for the bus. Some sitting, some standing. Relaxed. "Sir, Excuse me. When does the bus get here?" Try asking that question and you will get the blank look and the 500-mile stare. The bus gets here when it gets here and you're either on the bus or you're not on the bus. This is Africa. If this frustrates you then you will not like being in Africa.

So we drove around the spectacular rock formations of Matopos, and the aunties drank their beer, and they engaged in conversation with Precious in Ndbele. It became riotous and loud with laughter. They were very happy. I just drove around. This was her family. I was invited to belong to this family. I had to think about that.

Ndebele is a dialect of Zulu, or a separate language, depending on who you ask. It has some unusual click sounds that are very hard to imitate. Like you say amacimbe meaning eggs. Only the "c" is made like spitting into the wind. Native speakers do this easily, Learners are a source of much laughter. I often attempted phrases in Ndebele and was received with gales of laughter. It would come out like "I'm going to wash the goat." When I

meant to say I'm going to the store.

Damned difficult language. Fortunately English, thanks to Cecil Rhodes, is the language of education and government in Zimbabwe and everybody speaks it.

Status ranking. I learned by observation and by not asking questions. If I asked questions they would just tell me what they thought I wanted to hear. So here is the pecking order, as far as I could determine. Shona is the dominant tribe and the majority of the population in Zimbabwe. Ndebele is the minority tribe and less favored. Underneath that and lower are the migrants from Malawi, such as Precious and her family. Here are examples -- I did my banking at Barclays, the English international bank with a branch in Bulawayo, which is the center of Ndebele territory. But the manager, named Mubvumbi, was a Shona man. He knew nothing about banking, but he occupied a spacious office at the bank. It was a political appointment, because the Shona people control things, and the Ndebele people are subordinate to them. Underneath the Ndbele people are the immigrants from Malawi. Which is why some members of the Mataka family changed their last name, to fit in, to not being singled out as Malawians. So Precious was Precious Mataka to her family, but was legally named Precious Sibanda for official purposes. Mataka is a Malawi name that everyone recognizes. But Sibanda is Ndebele and as common is Smith or Jones. It gets more complicated, but I think we've had enough anthropology for today.

But wait, there are three more groups. On top and highest up are the white people, the remnants of old Rhodesia who had no political power since the revolution, but controlled the economy and managed the farm land. Under the white people were the Indians, a merchant class, who ran the grocery stores and other retail places. Nobody like the Indians. Precious's Uncle Ronnie worked at one of their stores. "Those Indians are too harsh. They don't pay him anything, " Precious said about Uncle Ronnie's Indian bosses. Underneath the Indians, but above everybody else were the Coloured people -- people of mixed heritage, of one parent European and one parent African. Light-skinned, like our President Barack Obama who is half-white and half-black. Most African people that you see on the streets of Bulawayo are full black and it becomes obvious when the lighter-skinned Coloured person appears.

Once I saw Precious looking in a mirror and I knew what she was thinking -- she wanted to have lighter skin and not be so black. She wanted to use the bleaching cream that some African woman use. The cream has very harsh chemicals. It is dangerous. I begged her to throw it away. "You are beautiful now, " I told her. What else could I say?

The End.

Expect another issue comes in a few days when I go to the Kwe Kwe Game Ranch to ride horses with the zebras and impalas.

All is well at our house. I made a list of projects to complete and games to play. We had several inches of rain yesterday. Everything is green ad bursting with blossoms and color.

take care,

Fred

9,829 words

FROG HOSPITAL -- March 21, 2020

Riding Horses at the Kwe Kwe Game Ranch.

By Fred Owens

They put me on a fast horse. Why did they do that? I told them I wanted an easy ride. They might have been having fun with me. He was a tan quarter horse named Jethro and he wanted to run. Just go flat out. A really good ride for somebody who knew how to ride. I was hanging on for dear life.

And who names a horse Jethro?

Anyway, it was a bone-jarring experience. I let him run and just held on. I saw zebras grazing and impalas leaping, antelopes I didn't know the name of and a giraffe. The game ranch had thousands of fenced acres. Stocked with zebras. You can keep zebras fenced in if you feed them and give them plenty of room. Impalas make good targets for predators (leopards) and poachers with a taste for antelope venison. You need a good rifle to protect the impalas. Nyama they say in Ndebele. it means meat. Zimbabweans love meat, from a cow or a goat, but from wild game as well. Tourists see an impala and take photos. Local people (aka "natives") see an impala and it looks like dinner to them.

How about wart hogs? The wart hog is so ugly that it's cute. They killed a wart hog for the BBQ when the backpackers came on their mangy, dirty old bus. These young and poor travelers had not bathed since Tanzania, but they drank plenty of beer in the interval. Partying with these idiots for one night was enough for me. And BBQed wart hog is one tough piece of meat. Flavor yes, but my teeth aren't strong enough to get it down. I would still be chewing if I hadn't spit it out behind a bush. Instead I filled up with potato salad and Bohlinger's Beer, trying to enjoy the company of drunken Australian college students out on an adventure trek.

The next night my hosts put me in separate housing, in a thatched tree house over-looking the swimming pool and near the main house. It was quiet up in the tree. The backpackers were all white people. My hosts were white people. That's why I was there -- to spend a few days with my own kind.

We ended the last installment of this African story, with this lament --

Once I saw Precious looking in a mirror and I knew what she was thinking -- she wanted to have lighter skin and not be so black. She wanted to use the bleaching cream that some African woman use. The cream has very harsh chemicals. It is dangerous. I begged her to throw it away. "You are beautiful now, " I told her. What else could I say?

What else could I say? I did tell the truth when I said "you are beautiful now." I was sure of that. But how could I even know the smallest part of what a poor, young African woman sees when she looks into a mirror? What was she thinking? Or was she even thinking? Her face was like a mask, unknowable. I could not read her. I was smart not to try. Except that one time, seeing her look into the mirror and I was moved to sorrow, because you gotta love who you are, and what you see in the mirror is not who you are. Except she was pretty. I could say that. "You're pretty, but what else do I know about you?"

I sat at table with the white ranchers, using napkins on sturdy china plates. They were stocky people, the man and the wife. Wide and strong. He wore short shorts which showed off his well-tanned legs. And sandals. In Zimbabwe high status men wear shorts and sandals. Danny, his name, had grown up on the ranch. "We are Zimbabweans. I was born here and so was my Annie. This is our country, I have no other country but Zimbabwe and this is my farm. It was my grandfather who started it, and then my Dad and me. We built the fences and the barns. We moved the earth and made ponds and put in irrigation. The revolutionaries say we stole the best land from the natives. Rubbish. We made it the best land with our labor. I'm a white African and this is my home." So Danny said as he sat in hi recliner after dinner. We were watching the BBC News from his big screen satellite television. Annie was coming in and out of the kitchen and giving kind instruction to the help. My comfort was established. And the lazy dogs sprawled at our feet. Life was good in Africa if you owned a ranch.

But, I interjected, you have a swimming pool and the local people have a cold water pump. The local people was his jargon for the workers who occupied a thatched roof village of 250 souls not a hundred yards from the big house.

"Yes, We have a pool and they have a pump. But I paid for it. I built that well for their water. And I have the water quality tested at times. They have good drinking water even in the dry season and they don't get sick. It is in my own interest to see to it that they are well and working. It is my responsibility. Everyone on this ranch has good water. And they say we are racist because we have a pool. Bah. We grow the food. We feed everyone. Because we want to get rich? No, the work is too hard. No, we feed the people from our hearts desire to do a good thing. No one is hungry in all of Zimbabwe, except some small tribes along the Zambezi River. But no one else is hungry because of farms like this. And we export maize to other countries, to Zambia and Mozambique. I'm very proud of that. And the government wants to take our land and give it to the local people.

"But they are the true immigrants. All these farm workers come from Malawi. Malawi is too poor. They don't even have shoes in Malawi so they come here because they can make money, doing work that Zimbabweans won't do at these wages."

But you could pay them better and the Zimbabweans would do they work at better wages.

"Would they? I doubt it. This is a good farm, but it's not from nature, it's from men like me who made the land productive, to feed people. No, I sleep well at night and I enjoy my TV and my beer."

Danny, you make a good point. This is a good farm and I hope you can keep it. I enjoyed having dinner with you and Annie. I will sleep with a full belly tonight.

And I did see his point. But I also saw Precious looking into the mirror that day and wishing her skin was whiter. Wanting to be whiter. I told her she was beautiful and that's all I said. She threw away the bleaching cream because I asked her to, but otherwise I did not expect her to change,. I did not expect Danny and Annie to change. I did not come to Africa on a mission. Unless I was kidding myself. Better get back on that horse and take another ride.

I now had a black girl friend and it was getting serious, a poor African woman with a big heart. Was I out of my mind? Did she even care for me at all? Well, sure, I was a nice guy and all and a white boy friend was better than a black man because I wouldn't beat her or cheat on her or take all her money. But that was in the larger scheme of things. Did she actually know me, and care for me?

Ach, I'm not going deep like that. Precious and I, we got along, we laughed together and her aunties liked me. I will ride the horse and have a few more evening chats with Danny and Annie and then go back to Precious in her little room on Airport Road in Bulawayo.

Correction from last installment.... Amacimbe means mopani worms in Ndebele. Amacimbe, or mopani worms in English, are a delicacy in southern Africa. They are grubs or caterpillars that live in the Mopani trees. The local people collect Mopani worms in their molting season. and they eat vast quantities. Fried in butter or lard, they come out looking like black shrimp. They have a powerfully strong flavor. I tried them at

Aunt Janet's house in Lobengula. Everyone watched me. Let's get the white man to eat Mopani worms, they told each other. Of course I ate one and then ate several more, just to show them I could do it. The taste was over-powering.

Next installment. Aunt Janet died. Even while I was at the Kwe Kwe Game Farm. Precious called me and told me she was dead. I came back straightaway. I had only just met Aunt Janet, but she seemed to be the best person in Precious's very large family.

Intermission. This very long story is less than half-way told, but we have all of the home isolation to tell it and that could go on for a long time, so we are taking a brief intermission and the next issue of Frog Hospital will be a report on local conditions from the coronavirus, as well a family news. We are healthy, and let's pray that health remains to protect us all.

take care,

Fred

11,454 words

The Good Doctor and Other Neighbors

By Fred Owens

The Africa story will continue in a week or so, but first we start off with news about our neighbors

A Good Doctor makes you feel good, even if the news is not good. Fran is an almost-retired pediatrician. She lives up the street a short ways with her husband Brian. They just returned from a visit with their daughter in Brisbane, Australia. They got off the plane in Los Angele and were not screened in any way, although Fran was not too disturbed about that. I think she is not easily disturbed in the broader sense. Fran and Brian invited us over to pick some oranges from their tree and to have a nice driveway chat at the right distance. News of their family and ours. Talk about how the fruit trees are doing. Fran says they have never had much luck with apple trees. Laurie said the opposite -- that her apple trees run pretty good, and, as if to prove it, she had brought a quart of frozen apple sauce from her own back yard tree.

There are only two important things to say about this. We kept our distance, that's one thing. The other thing was how calm I felt after talking with Fran about this, or about anything else for that matter. Good doctors like Fran make you feel good. They have training and experience to be sure, but it's a basic healing quality that good doctors have, and good nurses and other health care professionals. It's not magic. It's just some people have this quality about them and they become doctors and nurses and take the training to go with it. Healers. We need them now. And thank goodness we have them.

We will visit Fran and Brian again for more driveway dialog. In the meantime we stopped at the house next door. We saw Alex sitting in his garage with the door open, caressing a can of beer. He gave us a friendly hello. Alex is always out in his yard doing a project. Keeping busy, we can hear tools banging and motors humming. He sometimes keeps a horse in the back yard. The time was when most of the people in the neighborhood kept horses and there were easy trails about. But the increase in development closed most of these trails and you don't see horse riding like times passed.

On the other side of our house live dear friends Dede and Jim. We love going to their Super Bowl party every year. Jim is the football fan. Everybody else comes for the food and drink, and Dede can put on quite a spread. She and Jim own a well-known Italian restaurant in Santa Barbara called Arnoldi's. You think of a restaurant owner being all stressed out and quick-tempered. Not Dede. She presides with a principle of niceness. Nicetude, but nice all the time and everybody loves her. In the summer Arnoldi's has bocce ball tournaments in the back patio. If you ever visit Santa Barbara you would want to dine there. Try the calamari.

Across the street things are changing. Mabel Rye lived on this road longer than anybody, nearly sixty years or more, before there were any other houses. She and her husband Norris raised one son, Rory. She lost her husband some years ago, but Rory lived not too faraway and came every Sunday for her home-cooked dinner. You could see his car parked in the driveway on those days.

She lived alone for many years. We gave her many rides to the grocery store and swapped books with her. She is such a lively soul, almost turned 99 this year, but she is in the nursing home because of a broken hip and not coming back to her home. Her granddaughter was given the house and she is fixing it up. Mabel is very matter of fact about these changes. She takes it in stride with a surprising strength, an inspiration to me. Lately she has been talking about going to Heaven and what it's like when she gets there.

Well, those are some of the neighbors as we enter into our second week of social isolation. I have to say we don't feel lonely because of these friends who are only a shout away.

I will write more next time about our families here and there. Laurie's kids, my kids, and all the others.

The Plan is to put out two issues a week. One devoted to current matters in Santa Barbara. The other issue will be a continuation of the African story. Aunt Janet was my favorite of all Precious's aunties. I only knew her for a few weeks. She was barely past forty in age and she just died. That's African style -- sometimes people just die.

12,267 words

FROG HOSPITAL -- March 26, 2020

Aunt Janet Died

By Fred Owens

Zimbabwe, you can't get there from here. Not now. I looked it up. South African Airways has canceled all international flights from now until the end of May. So you are stuck here or stuck there, for now. Except I wasn't planning on going anyway. I just looked things up on the Internet to give you an idea of how it works. From Los Angeles to Bulawayo is 10,190 miles. Bulawayo is nine time zones earlier. That gets confusing if you want to make a phone call to Bulawayo, which you can do. Bulawayo is not the most modern city in the world, but they do have phones and the Internet, and Facebook, and a lot of other things.

I am not in touch with Precious herself, and let's keep it that way -- I mean in a good sense because I wish her all of God's happiness. But I am in touch with her cousin Grace who is reading my story about her family and seems to enjoy it.

But back to flying. South African Airways is the premier carrier in Africa and a flight from Los Angeles to Bulawayo costs $1,715 one way with stops in New York City and Johannesburg, if you could get there, but you can't because of current conditions which I do not need to explain.

The world map of virus cases shows a heavy concentration of victims in Italy, New York City, China, etc --- mostly northern developed countries. African countries show very few cases. I cannot find a reason for that and do not invite speculation. I would just say that Africa has enough problems, they do not need Covid-19.

The story I am telling takes place in 1997, the year Princess Diana died in a car crash. Princess Diana was a revered figure in Africa. She died on August 31, 1997, the day before Precious and I got married. I often saw her portrait on the wall in humble African homes, next to a portrait of Bob Marley.

In 1997 the Internet was just coming in. I could mail a letter from Bulawayo to anywhere in the U.S. for not much more than a first-class stamp. It took two weeks or less to get there. The postal service worked very well as far as I used it. But then there was email and my first use of that wonder.

To send an email, I wrote out my message in long hand and took it down to the Secretary Bird, a secretarial service in Bulawayo that made copies and stuff like that. They would copy my message on the computer and send it to my daughter's email address at Oberlin College. Cost about $1 US. My daughter Eva and I kept up a lively chatter.

I am mentioning all these interesting details as a way of getting myself back into writing the story. It's an effort in time-travel, in order to remember the events, which I have altered somewhat, because this is not a faithful memoir, but a story, an African story, which is best achieved by not a strict adherence to facts. Facts, which I explained in an earlier episode, are hardly welcome in Africa. At least I never found any, maybe a few at most. It's just different. I feel like I am indulging myself with this long introduction, but I have enjoyed telling it and maybe you have enjoyed reading it.

So here goes: When we left off last week I was riding horses at the Kwe Kwe Game Ranch and consorting with an old white Rhodesian farm family that owned this ten-thousand acre spread of grassland and pasture, with a much smaller portion of plowed fields for growing crops. Dannie and Annie owned the place. I forget their last name. And they felt justified to explain and defend their purpose and even their existence in Zimbabwe, talking to me in evening chats while we watched the BBC News on their satellite TV in their expansive, large living room.

I went there for a few days to be with white people. That worked. I felt at home with people who looked like me and understood what I was saying. After a few days of this, charged up as it were, I was ready to go back to Africa, that is, to Precious, who was Africa to me. Then she called long distance and said that Aunt Janet had died.

I had only met her Aunt Janet a few times, but I was impressed by her sheer vitality, her radiant smile and her copper-colored skin. I was to learn about all the aunties and uncles, but Aunt Janet was the first. And then she died, just like that. It made no sense. Precious called me to tell me the news, so I left the next morning. Dannie, my host, gave me a ride into Kwe Kwe town where I could catch a bus. "So, you're going back to see your girl friend," Dannie said, with a knowing smile and I caught his drift. I might stay on the ranch a while longer, send my regrets to Precious, pack up my things and take the next plane back to the states. I would have said that Precious and I had a nice fling, but it was just one of those things. That could have been my choice. I looked back at Dannie as he drove across sunlit pastures to the farm gate and then down the two-lane highway into Kwe Kwe town. Out of earshot from his wife Annie, he could have told me his own story with black women. "Plenty of white men come to Africa and do what you have done. Why not call it a win, and go back home. You got off easy." All in that look he gave me when he said "So, you're going back to see your girl friend."

Yes, I was going back, to a funeral. I wanted to know why she died, because she looked so healthy, but Precious said, "Otherwise she just had cancer." I didn't believe that. Foolishly, being new to Africa, I was looking for a reason. I wanted an explanation. But Precious's answer explained nothing. In Africa, people just die. Sometimes they get hit by a car and die. Sometimes they live to be very old and die of old age. But sometimes they just die. That was Aunt Janet. She was so beautiful. We went to Mr. Mataka's house in Luveve for the wake. Mr. Mataka was the father of Aunt Janet and the grandfather of Precious.

It was a small house of cemented cinder blocks, cool inside on hot days for having thick walls. Three rooms, a bedroom, a dining-living room and a kitchen. Large numbers of people lived there and slept on the floor at night. The kitchen had a cold water tap, a hot plate for cooking and heating water, and a cooler for selling beer -- which was Aunt Margie's evening occupation. Not thirty feet from the kitchen door was a well-used but very clean toilet in a small water closet. A flush toilet, because even though people were poor in Bulawayo, they had good plumbing and year round clean water.

The living room held the casket. On trestles. All the furniture -- the couches and chairs -- had been moved outside to the one side of the house where the men gathered around a small vigil fire. On the other side, the kitchen side, the women sat on the ground on mats.

The casket was in the living room on trestles. The cupboard with bric-a-brac was covered with a cloth. The casket was open and Aunt Janet rested so beautifully on her back, her hands folded, her eyes closed. She wore a fitted lace cap. There was no service or prayers or singing, not Catholic nor Moslem although the Matakas claimed both traditions. But it's a funeral, and you don't get to ask questions like are you Catholic or are you Moslem because you can't be both.... But I guess you can be both in Africa.

I fit in with the men's group. Mr. Mataka, the grandfather, indicated a seat on the sofa for me to occupy. He and I did not speak that night although we had many conversations later on, but it was his daughter's funeral and he was somber. . I enjoyed the flickering flames of the small vigil fire. The men talked softly for several hours. Precious was over with the women.

Man, just when this was really getting good I have to stop. We are at 1,500 words, and this email format doesn't like to get any longer. So I will continue writing this and send you the completion of this African funeral story in a few days.

Stay healthy,

Fred

13,754 words

FROG HOSPITAL -- March 30, 2020 -- unsubscribe if you wish

Aunt Janet is buried. Precious and I become engaged

By Fred Owens

The next day we buried Aunt Janet in the Luveve Cemetery. She was Janet Mataka, from Zimbabwe and Malawi, sister to Molly, Margie, Jennifer and Winnie. Her brothers were Peter Lovemore, Smiley, Milton and Ronnie. Her father was Mr. Mataka, that is, Patrick Lovemore Mataka, of Zimbabwe and Malawi. Janet was predeceased by her mother Grace, from Plumtree.

Tanti was one of her children. Tanti had seven children by almost as many fathers. "She can't use birth control," Precious said and laughed. She explained that this had something to do with witchcraft. Tanti loved babies and she was always smiling and laughing, skipping around the house in her bare feet even on the day of her mother's funeral. "She is just that way," Precious said.

The Matakas borrowed a pickup truck to carry the coffin, which was small and simply made, made to order I'm sure because it fit Aunt Janet's small body so securely. That felt sweet to me, that they built a coffin just for her. They loaded the coffin on the truck and the school bus pulled along side. The Matakas chartered the bus to carry everybody out to the grave, about fifty people boarding the bus late in the morning on a pleasant day in March, 1997, in the township of Luveve, in Bulawayo, the regional capital of Matabeleland, in Zimbabwe, Africa. The ski was blue and the breeze was gentle. People were nice to me, not gawking, but giving me no special attention. I was just there like anybody else and I appreciated that kind of informal welcome. I've always liked funerals, for just that reason, you can meet people in a good way. Now I remember that no one was very tall. Not the men or the women. I'm five-foot ten and no one was taller than me, except Francis, a nice young man, son of Smiley. But Smiley himself was shorter. Milton was short. Ronny was short. All the brothers were short, except Mr. T who didn't come to the funeral. Mr. T was Precious's father and nobody liked him. That's my own opinion. I know I didn't like him. Mr. T was tall and wide, very strong and very black. It was just as well he wasn't there, because he would have disturbed the gentleness of the burial.

The field was wide and grand. The earth was clay red like a charred cooking pot. The funeral party looked small in such a large field of graves. The weeds were here and there poking through the hard clay. The earth was freshly dug up by the grave site. The new earth was crumbly and even sweet. At another time and place the Matakas would plant sweet potatoes and maize in soil like that, freshly dug in a pile.

The sky was blue and the sun was not harsh. I counted four other funeral parties going on. This was 1997 at the height of the AIDS epidemic. No one talked about that. The Matakas did not ever talk about it. People died and that's all. Someone read a prayer. as we gathered around the coffin. Precious stood next to me in a flower print dress. She had been calm and even smiling, but of a sudden she broke down in a wail and threw herself on the coffin with loud tears and groans. "Oh Mama," she cried. "Oh Mama, why did you leave us?"

I was stunned by her ferocity, it was as if she spoke for the whole family, because there was no weeping except for Precious and she wept for us all. Even me. Then they lowered Aunt Janet's coffin into the ground and we shoveled the freshly dug dirt to cover it up and bury here. Buried forever, back to the earth. It was all so simple.

After the funeral Precious and I returned to her rented room on Airport Road. A few days later we decided to get married, to become engaged. I promised to buy her a ring. This made her very happy. The next day we visited a jewelry store in the downtown area. It was plush. The salesman was very polite, showing us velvet trays with rings of various sizes and prices. He didn't ask how much money I wanted to spend, but he made a good guess. The rings he showed us were up to $500 in cost. Precious looked them over quite carefully. She chose not the cheapest and smallest diamond, but one of lower price, at $150. She did not choose the biggest one and I breathed a sigh of relief. Maybe she knows what she's doing, I thought. What's a ring anyway, but a bauble? It seemed like the right thing to do.

"We will rent a house and live together for a while," I told her. "If that goes will, we will get married." She nodded her head while looking at the small shining stone on her ring. This was one of Precious's supreme qualities. Even in shopping for a ring she did not take very long to make her choice. Did she understand what I meant by engagement leading to marriage? No, maybe she understood nothing about me, and me her, but she had courage and that same spirit of vitality gotten from Aunt Janet.

Aunt Janet was mama to Precious. I should explain. The aunties are called mama because they are almost mamas as we would say, and the uncles were addressed as baba meaning father. Being engaged to Precious, I became umkunyani or son-in-law. And the aunties and uncles became mamazala and babazala, which is mother-in-law and father-in-law.