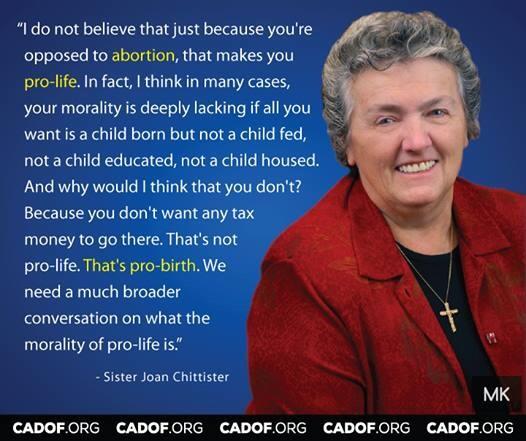

Compendium Of "Pax-Barbaria" Posts About Abortion, And The Indispensable Distinction Between "Pro-Life" And "Pro-Birth"

Reprise: "So Banning Guns Won't Prevent Gun Violence But Banning Abortion Prevents Abortion"

Homosexuality, Lesbianism, Abortion: Christians Ignore Jesus' Direct "Commandments" But Are Punctilious About Things He Never Said

GUEST ESSAY

I Couldn’t Vote for Trump, but I’m Grateful for His Supreme Court Picks

Ms. Bachiochi is a conservative legal scholar who has argued that Roe v. Wade should be overturned. She is the author of “The Rights of Women: Reclaiming a Lost Vision.”

As a pro-life voter living in heavily Democratic Massachusetts, casting a vote for president feels like a deeply inconsequential act. After all, the pro-choice candidate carries the commonwealth handily every four years. That said, over the past two presidential election cycles, I felt a strong sense of relief that I was free from the hard trade-offs of voters in battleground states and could just cast my vote for a write-in candidate.

Yet listening to oral arguments in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization last week, I realized more clearly than before how grateful I am to those pro-lifers who did what I did not, would not, could not: cast a vote for Donald Trump.

Politics is an art of prudence, and what I regarded as a deal with the devil they took to be a prudential act to achieve an essential end. For ending the abortion regime must be the keystone of standing against the individualistic libertarianism that characterizes our politics, left and right — and privileges the powerful over the weak and dependent. Ironically, and perhaps accidentally and certainly boorishly, Mr. Trump may have brought about what others could not.

Despite the manner, meanness, even maladjustment of the man — and despite the fact that he remains an ill-suited representative of our cause — Mr. Trump kept his promises to pro-lifers, nominating justices who now appear poised to overturn Roe v. Wade. While oral arguments are no perfect indicator of how the court will vote, Justices Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett, all appointed by Mr. Trump, seem ready to join Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito (and perhaps Chief Justice John Roberts) in sending the issue of abortion back to the people to resolve. While Justice Kavanaugh homed in on the Mississippi solicitor general’s argument that the Constitution is neutral on abortion, Justices Gorsuch and Barrett (as well as Chief Justice Roberts) worked to discern if there was any way to uphold the moderate Mississippi ban without striking down both Roe and Planned Parenthood v. Casey. (Both sides agree: There is not.)

If Roe goes, the pro-life movement can begin where it left off in 1973, working to convince fellow citizens (especially in blue states like mine) that we owe dependent and vulnerable unborn children what every human being is due: hospitality, respect and care.

But it’s not only that. Mr. Trump’s economic populism (at least in rhetoric) blasted through the libertarianism that has tended to dominate the G.O.P., a libertarianism that has made the party’s alliance with pro-lifers one of strange bedfellows indeed. If the G.O.P. wants to be of any relevance in a post-Roe world — after all, with Roe gone, those single-issue voters will be free to look elsewhere — it will have to offer the country the matrix of ethnic diversity and economic solidarity that Mr. Trump stumbled upon, but without the divisiveness of the man himself.

So what is the path ahead that he has now likely made possible? A post-Roe America will need to move beyond its wrongheaded obsession with autonomy. It will need to align both its rhetoric and its policies better with the realities of human existence and so should work to bring forth a renewed solidarity instead. We humans are not best understood as rights-bearing bundles of desires who progress through life by the sheer force of our autonomous wills. We are beings who are deeply dependent on one another — first and foremost for our very existence, as we did not come to be by an act of our own will, as well for every other good in life.

A world without Roe is a world lived in the reality of this existential interdependence, since none are more dependent than unborn children on their mothers. And as this dependence rightly calls forth maternal duties of care, so too does the mother’s greater vulnerability in pregnancy, childbearing and, should she opt for it, child-rearing place demands on the child’s father and society at large. The reknitting of these interweaving obligations — these solidarities — is the next political and cultural frontier. And the G.O.P., with its eyes newly opened to the threats of globalization and technocratic rule to the essential goods of the family, is poised to take it on.

The Democrats were once a closer fit for the solidaristic vision, which is why before Roe, pro-lifers once happily made their home in the Democratic Party. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s party was one that long sought to put the culturally essential caregiving, character-shaping work of the home at the very center of the economy, ensuring that families enjoyed economic security while they did that most important work. Democrats once sought a family wage and saw the importance, as the Progressive-era feminist reformer Jane Addams put it, of the “family claim over the social claim.”

But today’s Democratic Party — though rightly intent to provide robust economic support to struggling families — seems also intent to contract out the nurturing of infants and toddlers to “caregivers” rather than attempt to ensure, as their predecessors did, the kind of economic security that enabled (especially) mothers to care for their young children themselves.

Support for the abortion license over the past half century helped transform the Democrats from the party of the family wage to the party of academic, technocratic and corporate elites. The abortion regime has been deeply complicit in preserving a modern economy built not around the needs of families but on the back of the unencumbered worker who is beholden to no one but her boss.

Individual and societal reliance on abortion for women’s participation in economic and social life was the linchpin of the Supreme Court’s decision to reaffirm Roe in its 1992 decision Planned Parenthood v. Casey. As such, it was perhaps the strongest argument in the abortion-rights lawyers’ arsenal at the Dobbs oral arguments. But as even Planned Parenthood’s Alan Guttmacher foresaw in a 1968 speech, reliance on abortion as a backup to contraception tends to disincentivize contraceptive use and otherwise increase sexual risk taking, with women, not men, left to manage the asymmetrical risks.

Meanwhile, Casey’s claim that society has relied on abortion for women’s progress at once discounts the legion of anti-discrimination laws passed over the past century — while capitulating to the demands of an increasingly hegemonic market. After all, easy access to abortion (not to mention egg freezing and other technopharmacological interventions) helps businesses ensure that women are readily available to meet the all-encompassing needs of the globalized marketplace, thereby delaying real accommodations for time-consuming (and sometimes unexpected) parenting, especially for those women at the lowest socioeconomic levels in our society.

Such abortion-for-equality arguments are a far cry from the revolutionary vision Betty Friedan and Pauli Murray enunciated in the original statement of purpose for the National Organization for Women in 1966. Therein, one finds not calls for abortion on demand (or abortion at all) but instead for the country to “innovate new social institutions which will enable women to enjoy the true equality of opportunity and responsibility in society, without conflict with their responsibilities as mothers.” The statement urged not only robust anti-discrimination law, which would come to pass, but also better recognition of the “economic and social value of homemaking and child care,” which would not.

Indeed, the parasitic image that abortion rights feminists now offer of pregnancy is very different from what Ms. Friedan described in “The Feminine Mystique” in 1963 as the “biological oneness in the beginning between mother and child, a wonderful and intricate process.” As such, she sought better harmonization between work and home, suggesting, for instance, that universities hire female professors who have worked part time, as well as those “who have combined marriage and motherhood with the life of the mind — even if it means concessions for pregnancies.” Like generations of women’s rights advocates before them, Ms. Friedan and Ms. Murray were able to articulate a vision of women’s social and political equality without needing to rely on abortion to get there.

If the Supreme Court overturns Roe, the pro-life movement will need to redouble the efforts of pro-lifers on the ground who for a half century have offered support, assistance and care to pregnant women and their children, both born and unborn. And crucially, it should call men to task.

But it can also take its rightful place in the post-Trump G.O.P. — if the G.O.P., especially in red and purple states, can prove itself capable of policymaking on behalf of workers and their families. This will require that Republicans not fall back to doing the bidding of the business class whose own daughters will be, in the near term, anyway, a short flight or car ride away from legal abortion even after Roe.

This is all for the future. For now, we can say with surety and surprise, history will record that any of this was possible in 2022 because of a very unexpected figure, our 45th president.

Erika Bachiochi is a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center and a senior fellow at the Abigail Adams Institute, where she directs the Wollstonecraft Project. She is the author of “The Rights of Women: Reclaiming a Lost Vision.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.

No comments:

Post a Comment